|

|

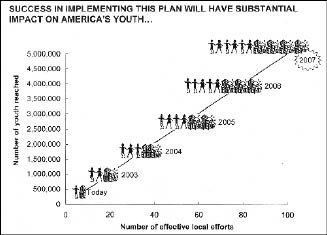

Source: America’s Promise, grant proposal to CNCS, 2002 |

Could it be a decade since the “ready, fire, aim” Philadelphia launch of America’s Promise – The Alliance for Youth? That giddy gathering known as the Presidents’ Summit for America’s Future drew 3,000 invited guests, including President Bill Clinton, former President George H. W. Bush, and a cast of what passes for the nation’s A-list of youth services’ big guns. At stage center was retired Gen. Colin Powell, then basking in opinion poll approval ratings of more than 70 percent.

Since then, America’s Promise has taken up more positions than a mobile ICBM. Initially, the aim was to recruit volunteers. Within six months, it dawned on America’s Promise that the narrow view from down in the silo had missed the existence of tens of thousands of direct-service public, for-profit and nonprofit groups that reach – no matter how inadequately – most of the nation’s birth- to 18-year-olds. They number 73.5 million, with 17 percent growing up in poverty and 11 percent having no health insurance.

After a series of meetings verbose enough to produce a SALT III missile treaty, America’s Promise, with help from the Search Institute and others, came up with five promises.

Since then, it’s been one expensive and transient promise after another. Since the Philadelphia summit, which cost millions, America’s Promise spent at least $94 million from 1997 through 2005, according to its federal tax returns. There have been Communities of Promise, once allegedly numbering around 400; Promise Fellows, sort of Vista volunteers in coats and ties, whose members roamed about promising to do good; 125 Promise Stations, which broadcast America’s Promise’s saccharine, pain-free and tax-free solutions to serving the nation’s 12.5 million children in poverty; and Sites of Promise, basically any youth service program that wanted to be so designated.

Then you had your Universities of Promise, Congregations of Promise, Hospitals of Promise, Hotels of Promise, Restaurants of Promise, Pharmacies of Promise, Schools of Promise, (Military) Installations of Promise, Corporations of Promise and local Banks of Promise (promising, perhaps, to make sub-prime trigger loans to the parents of disadvantaged kids?). In 2000, the National Select Morticians “joined forces with America’s Promise” for – at least we hope – a dead-on-arrival of what could be called Morticians of Promise.

All of these promises and more were hauled around the we-care-about-kids circuit in the America’s Promise official Little Red Wagon by Powell and his wife, Alma Powell, now the group’s chairwoman.

These promise-makers, said a 2002 proposal by America’s Promise to the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS), “will be enlivened by the new context of President George W. Bush’s vision of a ‘culture of responsibility. ’ ”

Enter New Promise-Maker

Fortunately, the moniker Promise Keepers was already taken by a Christian group promoting faithful fathers, based in Nashville. That is also the hometown of Marguerite Kondracke (formerly Sallee), the America’s Promise CEO and a former staffer to Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) Kondracke was paid $313,956 in 2005. America’s Promise rejected a request to reveal her current salary, saying it would do so in May 2008, when its tax returns for this year will be publicly available.

Ordered in October 2004 to get the Little Red Wagon greased and rolling again, Kondracke has certainly kept one promise to the organization’s 34-member board of directors: Bring in the cash. In 2005, America’s Promise’s gross receipts totaled a handsome $27,849,968.

A decade ago, America’s Promise was sold to a dubious youth service field and its funders as a three-year rocket to the moon for neglected kids, financed by corporate America. Every child in need, so went the sales pitch, would get a volunteer/mentor and, presto, another American promise would be fulfilled. While service providers feared that the new entity would compete with them on their home turfs, America’s Promise assured all that there would be no covert missile launches aimed at the territory of the members of the National Collaboration for Youth, part of the National Human Services Assembly, or Leadership 18, a United Way of America affinity group of national nonprofits receiving United Way funding.

In its early post-summit years, America’s Promise spent about $6 million annually, none of it directly from Uncle Sam. But America’s Promise found that its well-paid staff of about 60 could not man its battle stations on corporate largess alone. In most years, about one-third of the organization’s spending has gone into public relations or “branding” activities.

Back in October 1999, Powell had told The New York Times, “The last thing I want to do is become another chirping pigeon on the Hill” for funding for children. Was it better to be a Bush pigeon at the United Nations in 2003, chirping about nonexistent weapons of mass destruction in Iraq?

By 1999, America’s Promise was already chirping sweetly on Capitol Hill and burrowing into the federal budget: It got $200,000 from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention and $2.5 million from the Defense Department. In 2000, Congress approved a request by President Clinton for a $7.5 million earmark through CNCS for national direct “innovative projects.”

By 2004, government funding accounted for just over 56 percent of America’s Promise’s revenue of $6,929,777. From 2000 through 2005, direct government revenue totaled more than $26 million, one-third of all its income during that period.

15 Million More Promises

On Ash Wednesday in mid-February, America’s Promise convened a “leadership forum” that it called the “15 Million More: A Blueprint for Action,” at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, across from the White House. The crowd of 120 was too polite to ask about those first 15 million: Was that dollars per year spent by America’s Promise, or promises kept to 15 million disadvantaged kids over the past decade? Or none of the above? Was the new blueprint a revision of the one done by PricewaterhouseCoopers in 1999, or the one done by McKinsey & Company in 2001?

No matter. The Bridgespan Group was there, with enough strength to crew a Nike missile silo. The Boston-based, self-adoring consulting firm has found the keys to philanthropic bullion, including over $16 million from The Atlantic Philanthropies (assets: $4 billion), America’s Promise’s biggest foundation funder. Says Dorothy Stoneman, President of YouthBuild USA and a forum participant, “Bridgespan has cornered the market on business planning.”

In a hall full of talented veteran facilitators perched on top of some of the nation’s largest youth-serving agencies – such as the YMCA, Boys & Girls Clubs of America and United Way), the Bridgespan Group took charge. Alan Tuck, a partner at Bridgespan, told the crowd he could just feel the energy in the room, said several snickering participants. (The press, i.e., Youth Today, was barred from the event). While few fear the wrath of America’s Promise and even fewer fear that of Bridgespan, the presence of Charles Roussel, director of the Disadvantaged Children and Youth Programme at Atlantic Philanthropies, drove into anonymity those most critical of America’s Promise and Bridgespan.

One top national leader was “singularly unimpressed” with Bridgespan, whose whopping fees are paid directly by Atlantic Philanthropies. Says another incredulous participant, Bridgespan’s staff “was there to take your coat.” Not that there was any need for a hat-check girl.

The actual planning had already been done by yet another consulting firm, the Maryland-based Sagawa/Jospin, run by two former Clinton-era senior managers at CNCS, Shirley Sagawa and Deb Jospin. Last year, CNCS provided, via a congressional earmark, $5 million to America’s Promise.

Safely sheathed in three layers of staff (America’s Promise, Bridgespan and Sagawa/Jospin), the group at the forum spent two days coming up with the obvious proposals: Expand children’s access to health care, and raise the nation’s high school graduation rate. Lo and behold, these would be the same two targets of major efforts in Congress and philanthropy. (“Ding-dong,” Gates Foundation; it’s America’s Promise and Bridgespan calling).

In an e-mail after the forum, Kondracke called the confab “the amazing 24 hours.” Others called it an amazing waste of money. Through her press office, Kondracke declined to say how much the meeting cost.

Finely Focused

In 2005, four foundations (Atlantic Philanthropies, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Annie E. Casey Foundation and an anonymous donor) put up $8.3 million for America’s Promise to launch a kids’ advocacy group called First Focus, essentially to convince the then-Republican controlled Congress to enact some form of universal health care for children. It seemed like a smart move at the time, but then some funny things happened on and off Capitol Hill, not the least of which was the November mustering out of the GOP majority in Congress. Picked to head the venture in mid-2005 was Christine Ferguson, commissioner of public health for Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney and a former GOP Senate staffer. At $228,086 per year, Ferguson proved to be an expensive dud.

Hired to replace her was Bruce Lesley, who worked for Sen. Jeff Bingaman (D-N.M.). As political luck would have it, America’s Promise is one very lucky group (in the bumbling tradition of Mr. Magoo), because Democrats now run Congress.

So when First Focus held its oft-delayed premiere event on Capitol Hill on March 15 to release its report, “Priority or Afterthought? Children and the Federal Budget,” expectations in some quarters veered toward the skeptical. The report, along with a companion study, “Kids’ Share 2007: How Children Fare in the Federal Budget,” written by the Urban Institute, trod the familiar woe-be-kids path. The hearing room was packed with 150 earnest, well-educated, well-paid and well-groomed advocates who were well-disposed to the message on offer. Only about six African-Americans and one Army colonel added a dash of color.

Breaking the conventional rules of engagement was Robert Dugger, chairman of the Partnership for American Economic Success. The former Banking Committee staffer to the late populist Sen. William Proxmire (D-Wis.) brought his old boss’s Golden Fleece Award piquancy to the assemblage. Dugger zeroed in on who was not in the room. “Where’s the U.S. Chamber of Commerce?” he asked. And the National Manufacturing Association, the American Bankers Association, and the rest of the corporations free-loading through the unconscionable U.S. tax code? One example Dugger cited was $300 million in annual tax subsidies for corporate jets.

America’s Promise’s Kondracke stood stone-faced against the back wall, as Dugger chastised the very groups that America’s Promise has long told its philanthropic patrons it would bring to the table on behalf of children.

Nose Knows (a party crasher this time) doesn’t expect to see Dugger behind an America’s Promise podium anytime soon.

Still, First Focus had the good sense to focus on a now-easy target: reauthorizing and expanding the State Children’s Health Insurance Programs. SCHIP’s policy and budgetary rocket is on schedule to hit the bull’s eye in this Congress. Success has many fathers. Count First Focus and its president, Bruce Lesley, among them.

Promise Weepers

One February forum attendee – Peter Goldberg, president of the Milwaukee-based Alliance for Children and Families – noted that it’s fair to ask, “What has America’s Promise accomplished in 10 years?” Says another participant, off the record, “That’s a question everyone asks.”

In reviewing an America’s Promise final project report on its annual federal earmark of $7.5 million, CNCS Program Officer Dana Rodgers wrote in October 2002, “The whole issue of what the net result of all these initiatives and activities is, and what discernable role is played by America’s Promise in … increases in service to, and by, youth is something that we find of major importance.” What, asked Rodgers, “is the ‘value added’ that America’s Promise brings to an already crowded table of youth-serving agencies both large and small?”

America’s Promise itself demurred on answering that and other questions last month, with an e-mail from Senior Vice President of Communications Patti Reilly saying, “Marguerite’s travel schedule won’t allow for a telephone interview” over a period of several weeks. Odd, because when Nose Knows called Kondracke’s cell phone, she answered and agreed to an interview – then, via her office, later canceled. Just another broken promise in the service of poor kids.

(To see the e-mail exchange between America’s Promise and Nose Knows, go to http://www.youthtoday.org/youthtoday, and click on “News Links.”)

In America’s Promise’s own “Key Success Measures” proposal, it lists “Establishing Youth As A National Priority” as its top goal. With America’s Promise unwilling or unable to defend its first 10 years and first $100 million-plus in spending, the appraisal of its effectiveness was left to others.

Jodi Grant, executive director of the Washington-based Afterschool Alliance, declares herself “a pretty big fan,” citing America’s Promise’s ability to “pull together the leaders.”

Goldberg speaks of “the barbell phenomena,” noting the high profile start in 1997, the in-between years that were “lower and flatter,” and the current, more vigorous regime under Kondracke. “I’m impressed by the energy,” Goldberg says. “You’ve got to admire her.”

Much of the current effort at America’s Promise is going into something called the 100 Best Communities for Young People, into which all of those now-abandoned Communities of Promise were “folded.” The 100 Best is really just a public relations-generating national contest. The judging – actually done almost entirely by America’s Promise staff, despite a roster of glam names as “judges” – was based solely on written proposals from the communities. That mimicking of federal grant-making procedures did not allow for any reality-testing in the communities entering the contest. Nose Knows will wait for the more scientific U.S. News and World Report rankings to be published some day.

Chirping pigeons notwithstanding, the final evaluation of America’s Promise will rest on its ability to persuade those business interests and the congressional agents whom Dugger spoke of to make children the nation’s top domestic priority. Says YouthBuild’s Stoneman about America’s Promise and its supporters, “Are any of these ‘advocacy’ groups willing to fight for bigger appropriations” for all disadvantaged children and youth?

In the first decade of America’s Promise, the answer has been to make funding for itself and career advancement the only thing worth really fighting for.

Contact: America’s Promise (703) 684-4500, http://www.americaspromise.org; Partnership for America’s Economic Success, http://www.partnershipforsuccess.org.