|

|

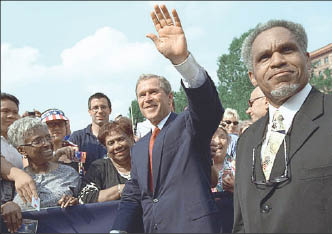

Old Friend: Former Philadelphia Mayor John Street, shown here with President Bush in 2001, boosted funding for Safe and Sound Photo: The White House |

For most of its 10 years, Philadelphia Safe and Sound (PSS) seemed as secure as a youth-focused nonprofit could be: It was locked into city funding and, maybe more importantly, it had political support from the highest levels of City Hall.

So it was stunning when PSS, which each year delivers roughly $50 million in public funds to more than 200 after-school, summer and youth development programs, decided to shut down last month – a victim of being seen as too close to those in power.

“The lesson I think I take from all of this is that … if you want to survive beyond the current [political] administration, that you establish and maintain a certain degree of independence from city administration,” said PSS Board Chairman Ernest E. Jones. “The difficulty with being so closely aligned with city government is that when you get a new administration in,” it is likely “to want to change things.”

PSS was established in the late 1990s with a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Urban Health Initiative, which funneled the money through the city to PSS. It later spun off into a nonprofit and enhanced its collaboration with the city. It grew in the early part of the next decade during the administration of Mayor John Street (D), serving as an intermediary between the city and youth-serving agencies, making grants to nonprofits, overseeing the management of those grants and providing support. Its role was similar to that of nonprofit intermediaries in other cities, such as The After-School Corp. in New York.

Fast Growth

In the eyes of many local observers, PSS was hurt early on by the perception that it served as a political patronage operation for Street, whose wife, Naomi Post, was appointed by former Mayor Ed Rendell as its first executive director. Post’s tenure ended in 2002, but that “aura” was “cast in stone,” said Anne L. Shenberger, the nonprofit’s CEO.

Still, PSS hummed along. Its funding skyrocketed from $2 million in 2002 to around $60 million for the last year with the vast majority coming from the city of Philadelphia and the state of Pennsylvania. The staff grew as well, from 16 in 2003 to 81 by the end of 2007.

Among other things, the organization developed annual Community Report Cards that graded youth health, safety and academic achievement on the neighborhood level, and it created a geographic information system that maps block-by-block needs in order to help agencies plan, raise money and develop programs.

On the other hand, PSS drew the kind of complaints that are often directed at big nonprofits that get a lot of government money. Jones, the board chairman, heard that some service providers saw PSS as an “800-pound gorilla” that was insensitive to funding other needy grantees, and that others thought PSS was “shrouded in secrecy.”

Even the board was concerned that all that money made PSS too beholden to the city. So when the city offered PSS an additional $30 million in 2003 to administer after-school programs – which at that time increased PSS’s budget 10-fold – the board considered “whether or not we should have said ‘no’ to that,” Jones said. “Since we get 95 percent of our funding from the city, that’s risky. If you don’t do what they want you to do, they can say, ‘Fine, we don’t need you at all.’ ”

Jones said the increased funding was distributed to providers for specific uses. “We just took over administration of those funds,” he said. “It’s a lot more work.”

Ironically, the real trouble began last year with what seemed like good news: Street, leaving the mayor’s office because of term limits, submitted a final budget plan that would increase PSS’ city funding for 2008 by another $21 million, to $75 million.

Trouble

That didn’t sit well with the incoming mayor, Michael Nutter, a Democratic city councilman who had feuded with Street for years. After taking office in January, Nutter rejected the increase. PSS had spent some of the proposed extra funds, so PSS grantees’ allocations had to be cut to absorb the loss.

|

|

Skeptical: Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter cut program’s funding. Photo: www.nutter2007.com |

The Nutter administration also instituted a cost-saving plan for after-school programs that involved moving many after-school and summer programs from schools to recreation centers. That sparked a debate about whether those centers could handle the load and protests from those who had been providing the services in schools.

Cheryl Weiss, executive director of Diversified Community Services, a PSS grantee, said her after-school and summer programs will be cut by $40,000, to around $380,000, over the next 12 months. “I don’t necessarily disagree with” the Nutter administration’s desire to try to serve more high-risk youth with its money, she said, but the sudden shift without consulting providers caused “enormous upset.”

Meanwhile, the Pennsylvania Department of Public Welfare launched an audit of PSS in concert with the Nutter administration.

The audit, released in April, found that the organization was overwhelmed by extraordinary growth; lacked a sufficiently developed corporate governance structure; had an innovative but complex organizational structure; and was “vulnerable” to breakdowns in administrative and fiscal controls.

“As a result,” the audit said, “there is significant risk that a portion of Philadelphia’s prevention programs are not currently serving the populations most at risk of delinquency or dependency while the overall service needs of such at-risk populations remain high.”

Shenberger, the CEO, said PSS took issue with “all” of the negative conclusions in the audit. PSS produced a point-by-point refutation more than 40 pages long.

In the same month the audit was released, the Nutter administration put the intermediary contract up for competitive bidding.

“Given all of the negativity surrounding Safe and Sound, there was no way that I thought we could successfully bid on that contract and get it back,” Jones said.

So in late April, the PSS board voted unanimously to shut down operations as of June 30.

Now What?

There are “a lot of lessons learned,” said Margaret Zukoski, associate director of the Pennsylvania Council of Children, Youth & Family Services, a statewide organization of 140 private direct services agencies. Most important, she says, is the need for “ongoing communication about the status of services and funding,” and for efforts to bring “everyone along so we can anticipate what issues may arise.”

Announcing with little warning that PSS funds would be cut off caused “unneeded stress and uncertainty” in the provider community, Zukoski said, and as a result, “some trust has been lost in the public sector.”

The city announced last month that the Philadelphia Health Management Corp. (PHMC) would serve as the new fiscal and management intermediary, taking over operation of all PSS-operated summer programs on July 1. PHMC, Nutter said in a statement, was chosen in a “timely and transparent manner” from six organizations that responded to the request for proposals.

The organization has no time to waste: It will have to run the summer program funding competition under newly established program rules, including the move to recreation centers.

Contact: Philadelphia Safe and Sound (215) 568-0620, http://www.philasafesound.org; Philadelphia Health Management Corp. (215) 985-2500, http://www.phmc.org/aboutus/contact.html.