Among trendy ideas in education and youth development — right up there alongside “growth mindset” and “grit” — is something called “design thinking.”

It comes from the world of product design, and a major advocate is the global design company IDEO, which defines the concept as “a human-centered approach to innovation.”

“Learn to solve anything. Creatively,” challenges the IDEO website.

That’s quite a big claim.

Now teachers are being led into workshops on the subject and some after-school and youth development organizations are beginning to spread the word. A conference held in early June by Boston After School & Beyond included a presentation on design thinking. And in Philadelphia, a consultant created a workshop to bring the Philadelphia Youth Network up to speed.

MIT’s course for education leaders says design thinking can transform the classroom. Stanford Business School offered executives a four-day immersion course in design thinking for $12,500 in September.

Is design thinking an overhyped idea — or can it really help kids solve problems?

How one youth organization uses it

Design thinking is a process that began to be employed by scientists, engineers and architects in the 1970s and 1980s. In the 1990s, the founder of San Francisco-based IDEO began applying it to business.

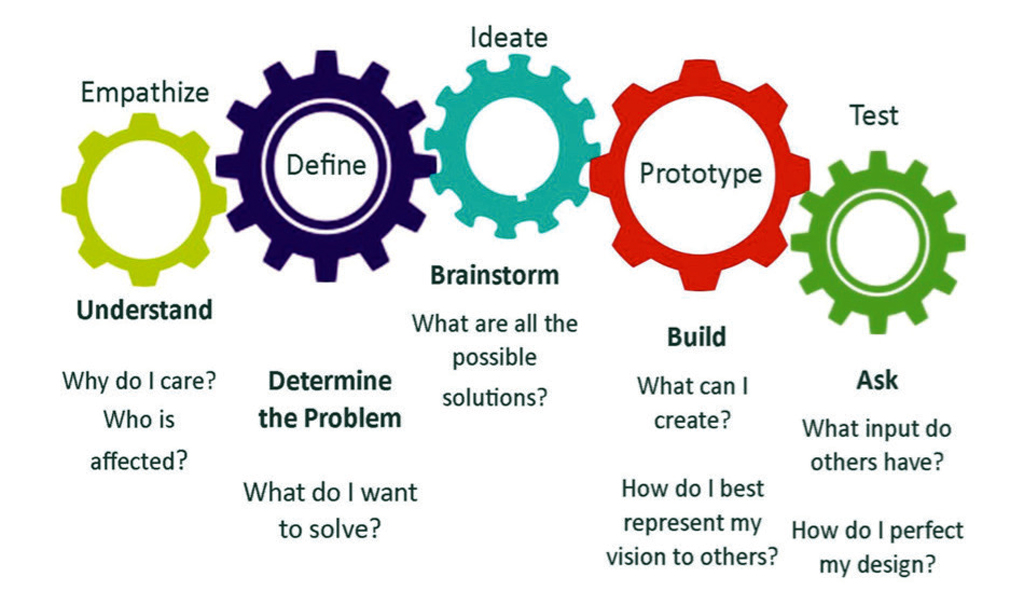

The process, which starts with gathering information and defining a problem, is sometimes summarized in the following five steps:

Lydia Emmons, director of college and career pathways at Sociedad Latina in Roxbury, Massachusetts, describes how the nonprofit serving middle and high school students employs this process. At Sociedad Latina, middle schoolers get academic and English language support in a STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art and math) program, while high schoolers learn about entrepreneurship. “The process of design thinking is used in both programs,” Emmons said. “Students develop a way of thinking they can take into the future.”

One way Sociedad Latina — where 75 percent of students are Latino, and 60 percent are English language learners — introduces the subject is through a project in which students help design another student’s workspace.

In step 1 (empathize), kids work in pairs and one asks the other a series of questions: What do you like and dislike about your space? Describe your best day at work. What could you do to make it more productive? Describe the things you do in that space.

The student gathers information by asking these questions and then reflects on what he or she has heard.

Then the student defines the problem (step 2) by writing a “needs statement,” filling in the following blanks: “_________ needs a way to ________ because they ___________.”

In the next step, the kids brainstorm in a rapid idea-creation session. They must come up with 25 ideas in a minute.

“It’s a new way of thinking for our students,” Emmons said.

Next, they move into the “prototype” phase (step 4), she said. They ask: “Out of these ideas, what can I create?” and “How do I best represent my vision to others?”

Students then build 3-D models of an improved workspace.

The final step is to test this prototype. The student asks the partner to give feedback. “Did the design solve the original problem?”

At that point, the design process could start all over, Emmons said.

“It’s a new way of problem solving,” she said. The process can be applied to larger community issues or to day-to-day life, she said.

Students can apply design thinking to challenges such as filling out a college application or figuring out how to get financial aid for college, Emmons said.

“It becomes a second nature,” she said. The organization measures its impact after youth graduate: 84 percent of its alumni are succeeding in full-time employment or postsecondary education, according to Sociedad Latina’s latest published impact report.

In the program, students identify an issue in their school or a need that another young person might have, she said.

“What are my lived experiences? Where do I see challenges and opportunity? What do I want to solve?” they ask.

They might look at their school cafeteria and consider whether it could be redesigned to better meet the needs of students, she said.

Middle school students in Sociedad Latina’s STEAM Team built a projectile and then launched it. They were learning what forces act (speed, length and weight) on the projectile to get it to the target point.

“It’s a process in which students are able to empathize,” she said. They understand a problem or issue, why I care and who else is affected, she said.

Emmons said the skills developed through design thinking are linked to the evidence-based Achieve, Connect, Thrive (ACT) Skills Framework developed and used by Boston After School & Beyond. The skills are those that evidence suggests are needed by students in order to succeed in school, college and career.

Design thinking has been described as a process that elicits empathy, encourages creative thinking and allows for plenty of failure on the way to a solution.

Architects come up with ideas using this process. It’s also used by entrepreneurs who are developing technology to solve problems.

But the individual components of the process aren’t particularly new. For example, the first steps of the process have been used for some time in service learning projects: acknowledge a problem that exists and figure out possible ways to address it.

Inflated claims

To Mike Rose, the problem is that education buzzwords like design thinking, grit and mindset make inflated claims. They are presented as if they could solve Middle East conflict or put a human being on Mars, he said.

Rose is research professor at UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies. His books include “Why School: Reclaiming Education for All of Us” and “Possible Lives: The Promise of Public Education in America.”

“The problem is the way [these ideas] get presented as the new magic bullet,” Rose said.

“They all have something going for them,” he said, but hype begins to build.

“Then they become a source of commodification,” he said.

Workshops are offered, conferences and materials are produced. Money is made.

There is overreach, he said.

Another problem occurs when these ideas “are targeted to poor kids and substitute as solutions for the very real needs in low-income schools and communities,” Rose said.

Teaching grit as character education, for example, has been directed at low-income children in place of addressing the very real inequalities they face, Rose wrote in a blog published in the Washington Post in 2015.

“Anyone who has worked seriously with kids in tough circumstances spends a lot of time providing support and advice, and if grit interventions can provide an additional resource, great,” Rose wrote in the blog. “But if as a society we are not also working to improve the educational and economic realities these young people face, then we are engaging in a cruel hoax …”

Rose does not argue against encouraging perseverance in kids. The basic idea has a place, he said.

“One of the many frustrating things about education policy and practice in our country is the continual search for the magic bullet — and all the hype and trite lingo that bursts up around it,” Rose wrote.

Teacher and writer Jessica Lahey, in a January article in The Atlantic, said the ideas of grit, mindset and design thinking have gotten cloudy and confused. In her view, they are victims of their own popularity.

Design thinking is not a curriculum, but a process for problem solving, and as such, can be useful, her article said.

Creative thinking

Pete Evans encourages design thinking when he takes a mobile STEM classroom around to schools, 4-H groups and summer camps.

Evans is a senior lecturer in industrial design at Iowa State University, and his mobile classroom is outfitted with workstations that give school-age kids a taste of 3-D printing, circuit building and virtual reality through Oculus Rift headsets. It also lets kids play with presenting data using computer graphics and animation, a method known as immersive visualization.

Evans said design thinking helps kids use the technologies more creatively.

In scientific inquiry, “there has to be both creativity using design thinking and critical thinking using the scientific method,” he said.

Science and engineering have led to a type of positivist thinking, Evans said, that sees solutions as either right or wrong. That’s a limited perspective, he said.

Design thinking takes a look at different relationships, bringing in more context and fine detail, he said.

The components of design thinking, however, are already familiar to any educator who understands the basics of effective teaching, Lahey wrote: “start with empathy, move ego to the side, and support students in the process of failing often and early on their way to learning.”