Jason Herndon had walked past the Philadelphia Wooden Boat Factory, an old brick building in north Philadelphia, many times, thinking it looked like a hangout for high school students.

Last summer, when he was a rising senior at nearby Frankford High School, a friend invited him to an event sponsored by the Wooden Boat Factory. He learned that the building housed an after-school boatbuilding and maritime arts program.

He was interested, decided to join and right away found himself dragging a 300-pound rowboat out of a shipping container down to the public boat launch.

Feeling a little lost, he stepped into the boat with other high school students, and they awkwardly began to learn how to row together. Afterwards, he described the experience as awesome.

Herndon’s experience is an apt metaphor for the out-of-school-time program: Young people ages 14 through 21 — from neighborhoods that “face significant unemployment, high incidence of crime as well as substantial poverty” according to the organization’s website — are immersed in hands-on experiences through which they learn to pull together as a team and in the process develop competence and confidence in themselves.

At the Philadelphia Wooden Boat Factory, boatbuilding is an intentional strategy to help young people develop socially and emotionally. Hands-on work is the vehicle to get there.

A student clamps tapered pieces of wood together in a beginning stage of boatbuilding.

“When you engage in craft [work], the materials give you feedback in real time,” said Brett Hart, executive director of the 21-year-old nonprofit organization. “You develop an authentic sense of competence.”

Inside the old factory building, the aroma of cedar wood shavings fills the air. Three to four boats are taking shape at any one time, propped up on supports.

Recently participants worked on a 16-foot racing boat for middle-school students to sail. They also constructed an 18-foot rowboat for students in the organization’s watershed advocacy program.

“Every young person is making a contribution that is meaningful and profound … to someone else,” Hart said.

Gaining competence and making a contribution both lead to confidence, he said.

Dealing with challenges

The Wooden Boat Factory is located in a tough neighborhood in Philadelphia.

Poverty is a big issue and the schools are under-resourced, Hart said.

The area has a lot of violence inside and outside school, he said.

Each day after 3 p.m., students file into the building from nearby Frankford High and Mariana Bracetti Academy Charter High School. They get snacks in the kitchen, socialize in the lounge and then come together at 4 p.m. for a short meditative practice to let go of the stresses they may bring with them, Hart said.

Two students use a bandsaw to cut wood. Each boat is made of nine planks, giving students plenty of practice in cutting and fitting them together.

“Then we dive into the work,” he said.

At the start of the year, students begin with architectural plans and a pile of lumber.

Each day they see a blackboard with a list of the tasks that need doing. They choose their task and find themselves working in a small group.

They measure, cut, glue, plane and join.

“Our staff float around the room available to respond, to answer questions as needed to engage with students and support them,” Hart said.

The staff uses a motivational interviewing method that puts young people in a position of expertise and strength, Hart said.

“They ask questions that let the students solve the challenges in front of them,” he said. “Our work is very much centered in youth as experts.”

Eleven adult staff members oversee 82 student apprentices. Half the students come on Monday and Wednesday, the others on Tuesday and Thursday. Students receive a stipend each month.

Khalil stands next to a Point Comfort Skiff, designed by Doug Hyland and built at the Philadelphia Wooden Boat Factory.

In the summer, 30 are invited to work 20 hours a week in boatbuilding, sailing or exploring environmental science.

In addition, the organization offers a watershed advocacy program for high schoolers and a sail-making program for middle schoolers.

The boats at the Philadelphia Wooden Boat Factory are constructed with nine planks on each side.

“There’s a lot of opportunity for repetition,” said Emma Bergmann, a social worker who is clinical director and director of operations.

The first plank the students construct may not be made well. The next plank gives them a chance to do it better.

As they repeat the planking process, students can see the mistakes and figure out how to fix them. Repetition is a built-in method for gaining and improving their skills.

The work can also lead to frustration. Bergmann and the other staff are ready to discuss the situation and help students develop insight into their feelings.

Charles Smith is chief knowledge officer of the David P. Weikart Center for Youth Program Quality.

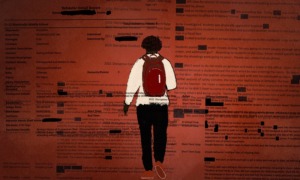

Students (left) in the Riverguides program at the Philadelphia Wooden Boat Factory launch a boat onto the Delaware River. Jason Herndon, in the red life jacket, joined the program his senior year in high school. In Riverguides, youth become environmental advocates and watershed educators.

“Active learning presents plenty of opportunities for frustration,” Smith said. Kids then can learn different ways of handling that frustration and managing their emotions.

“Active learning provides the opportunity to experience both frustration and support,” he said.

What is active learning?

Active or hands-on learning is about youth engaging with both materials and ideas, Smith said. It’s a method of engaging kids beyond concepts. It is both concrete and abstract, he said.

But it is more than simple exploration. “You’ve got to say what the point is,” Smith said.

“It’s not purely exploratory.”

The California 4-H Youth Development program describes a five-step approach for experiential learning, a more precise term for hands-on education: Experience, share, process, generalize, apply.

According to the organization, experiential learning engages young people by:

- direct hands-on activities or projects

- open-ended questions that elicit discussion and interaction

- active reflection and discussion

- making connections with “real-world” ideas or skills

- applying the new understanding to other situations.

Smith said hands-on learning motivates young people and gives them the opportunity to practice and demonstrate skills.

Kids are motivated when “they have more choice and control over … the learning environment,” he said.

He said they can practice new skills in a variety of ways, and they can show what they’ve learned, giving adults more ways to assess a young person’s knowledge than just standardized tests, for example.

He said out-of-school programs are designed to offer young people the opportunity to be successful, but kids may be dealing with a variety of stressors.

For example, they may be outsiders in affluent neighborhoods, be ignored in dysfunctional schools or live in neighborhoods without enough opportunity, he said.

When kids experience stress, it closes down learning, he said.

A hands-on learning environment “opens kids up,” he said. They can be more at ease.

The environment also provides adults the chance to step in and nudge kids or to “step back to let them have a lot of latitude,” Smith said.

Being with others, managing oneself

At the Philadelphia Wooden Boat Factory, students take part in a weekly workshop on social and emotional skills. They may focus on managing emotions, developing empathy or working in teams. They take part in an activity, reflect on it, discuss their thoughts and feelings, and then talk about the skill they have developed.

Hart, the executive director, said there’s a lot of space to process recent traumas. He cited a recent attempted rape at one of the high schools. Students have a chance to voice concerns about what’s happening in their lives, he said.

Students say they’ve learned a lot about themselves and others.

You learn to get along with people that aren’t necessarily part of your crowd, said Christopher Stewart, a junior last year at Mariana Bracetti Academy.

“Success is when you get a job done,” he said.

Students also learned how to deal with somebody who’s goofing off.

You have to tell them to “stop goofing around,” he said. Sometimes you might step aside to talk to them.

Casey Harkins, a senior at Frankford High, and Julisa Pantojas, a 10th-grader at Mariana Bracetti Academy, took part in the program last year. Both said they were quite shy when they began.

“It helped my people skills,” Harkins said. “I didn’t know how to talk to people.

“It helps you come out of your shell,” she said. “It made me feel like I belonged.”

Inside the old factory where students are working, there’s a whiff of an earlier era, a time when young men went to sea on hand-crafted ships.

Those earlier generations found adventure, developed identity, learned skills and built competence, Hart said.

“Identity and competence are incredible paths to healing,” he said.

The craft work associated with that time has nearly vanished, but crafts groups around the county “value it and are bringing it to the center of conversation,” Hart said.

“There’s a great counter-culture conversation going on about the value of craft,” he said. “We’re bringing that conversation to youth development.”