I was 10 years old when my mom started taking GED courses. She was 36.

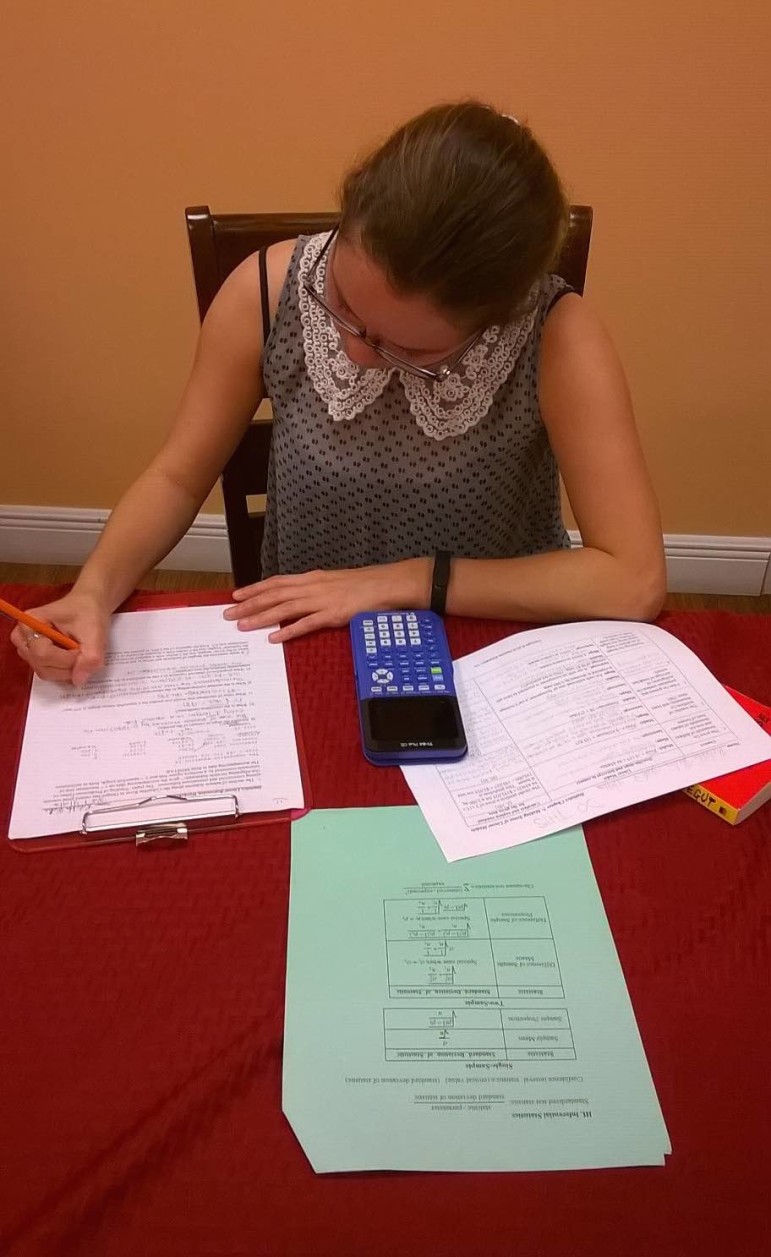

Each night after dinner, we would sit together at the dining room table to do our homework. My stepdad didn’t hide his discontentment that my mom was “wasting her time” studying. Still, she persevered.

It sure was nice to have someone sitting at the table with me, toiling away at endless math problems and the litany of spelling words. Though my mom had her own work to complete, she would take breaks from her assignments to quiz me on my words. I remember those flashcards well!

Steve Bardy SC ED

Decades later, as executive director of Children’s Home Society of Florida, I stood in the kitchen of our girls’ home in West Palm Beach, watching a couple of girls sitting at the dining room table completing their homework. Though the home had 12 girls, only two “had homework.”

In that moment, I saw my mom. I saw the trailer we lived in. I saw the arguments she had with my stepdad and her struggle to create a better life.

There, in front of me, I saw a cycle repeating. These girls did not have a mom or dad encouraging them to do well in school, nor did they have anyone connecting their education to employment opportunities — opportunities for a better life.

Fresh off a seminar where I learned about programs offering incentives to encourage youth not to run away from their group homes, I started thinking about how this concept could be used with our girls to encourage education and promote employment skills. It was so simple: Our girls could earn money based on their individual performance in school.

With Earn to Learn, the girls’ job is to do well in school. The better they perform, the higher their earnings. Each step reinforces the connection between education and employment. And for these girls, it provides a level of control in their lives that few youth in foster care feel they ever have.

Children’s Home Society of Florida, Earn to Learn program

Through the program, young people earn money for achieving grades in school: $20 for each A, $10 for each B and $5 for each C. A grade lower than a C is not compensated nor is money deducted. Super simple, right?

As we encourage young people to set goals for themselves, they are asked at the beginning of each quarter to commit — in writing — to a grade they will earn for each class. Daily, youth are encouraged to study and, if they need a little extra help, to participate in tutoring. Staff members ask about homework, talk about their classes at dinner and offer assistance. Let’s face it, sometimes we forget how hard ninth grade was!

At the end of each quarter, participants provide their grades to staff. The earned grades are then compared with the grades the girls originally committed to, encouraging them to set and achieve their personal goals.

It’s important to remember that we need to meet youth where they’re at — not where we want them to be. If a student earns a B in geometry, they must commit to earning at least a B the next quarter.

By the same token, we encourage small victories. If a young person is failing a course, we ask them to strive for a C rather than commit to an A.

Reviewing grades one-on-one at the end of the quarter is incredibly important, too. Deviations from one quarter to the next can be an indication of challenges, issues and even positive influences in daily life. When a teen who loves basketball receives an F in team sports, it’s time to have a conversation. When someone drops from a 3.0 to a 1.8 in a quarter, don’t ignore it.

And when a student starts with a 1.5 and earns a 3.5, it’s cause for big applause!

Once grades are provided, youth receive their earned money in the form of gift cards. It’s theirs to spend as they wish. Most use it to pay their cell phone bills.

At the end of the day, each interaction with the youth adds a chip in your bucket of trust. One day, you will be asked to write a letter of recommendation for college or receive an invitation to a high school graduation. Those are the days you hold on to tightly.

Each time I witness a young person realize how smart they are and understand how much they can achieve, I think back to that small dining room table, where I sat each night doing homework with my mom. Her encouragement and commitment to education changed my life.

At 54, my mom earned her bachelor of arts degree.

Steve Bardy is vice president of operations for the Children’s Home Society of Florida. He has created several innovative prevention programs for the Florida Department of Children and Families, Public Health and the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice.

More related stories:

Will ESSA Raise College Access, Track Graduation Rates for Foster Youth?

Federal Education Law Delivers Vital Protections for Foster Youth