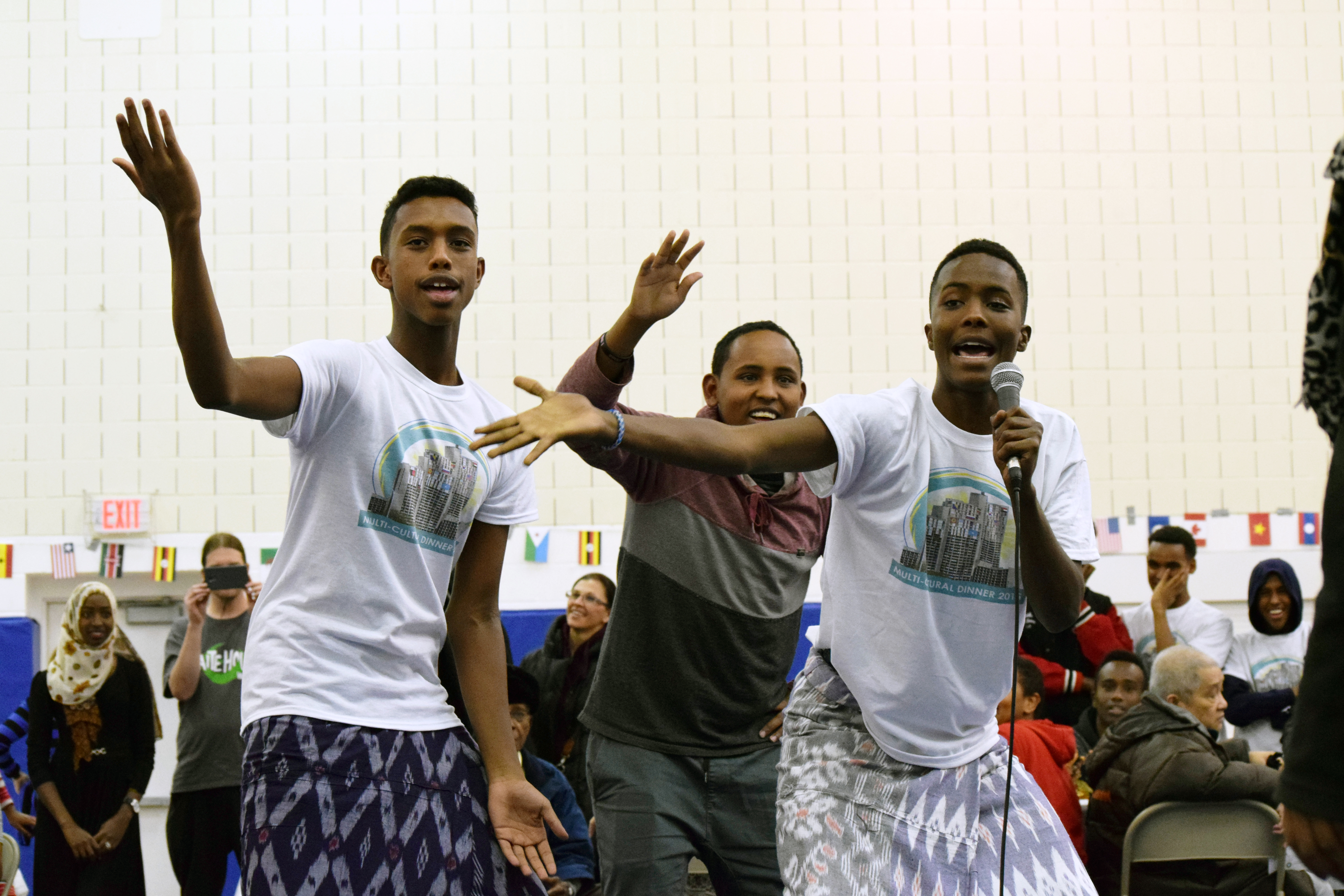

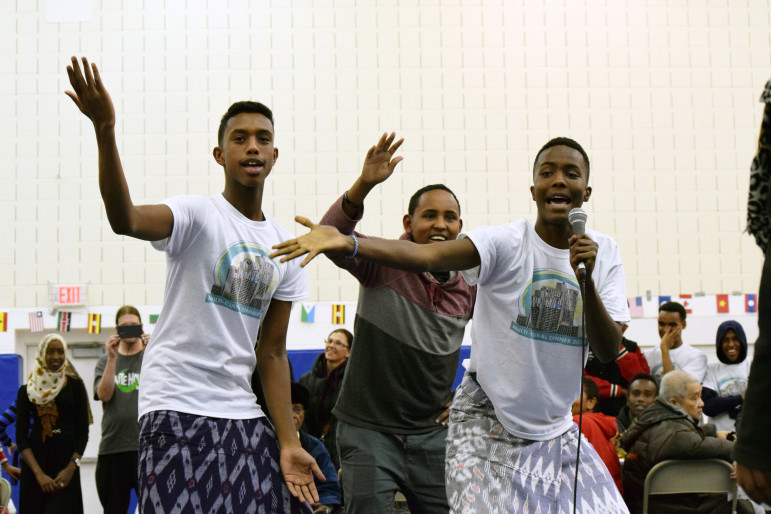

Photos by Pillsbury United Communities

Youth perform at the Annual Multicultural Dinner of the Brian Coyle Center in Minneapolis, which offers numerous activities to youth in the city’s Cedar Riverside neighborhood, many of whom are Muslim. From left are: Abdullahi, Abdirizak and Mohamed (with microphone).

Early in December, Abdirahman Mukhtar was driving two of his young sons to school in Minneapolis when a news story came on the radio.

It was about the political furor over Muslims in the United States.

His 7-year-old piped up: “Dad, why do they hate us? We’re not all bad people.”

Mukhtar almost swerved the car over to the side of the road to talk to his son.

“Not everyone hates us,” he began.

Mukhtar, who came to the United States at age 17 from East Africa, is the youth program manager at the Brian Coyle Center in Minneapolis. It’s one of six centers in the city run by Pillsbury United Communities, which offers programs, neighborhood centers and social enterprises in underserved areas of the city.

Mukhtar and his wife have four children.

“We as Muslim parents are dealing with this,” he said, of the hostility toward and misunderstanding of Muslim kids.

“People stereotype them,” he said.

“They are American,” he said. “They were born here.” But what happens in San Bernadino, California, and other places affects them, he said.

More than half of Muslim students ages 11 to 18 report having been bullied because of their religion, according to a 2014 survey by the Council on Islamic-American Relations in California. This rate is twice as high as the national average of kids who report being bullied at school, the report said.

In a recent incident, a sixth-grader at a New York public school was grabbed by three boys at recess who tore off her headscarf, “Inside Edition” reported.

Muslim youth need a safe environment — a safe youth-friendly space — which allows them to give voice to their experience, Mukhtar said.

“Our program is a home for them,” he said. At the neighborhood center, they find trusted adults

The youth program at the Brian Coyle Center serves 250 youth in grades K-12 in the Cedar-Riverside area of Minneapolis. Nearly all are from East Africa and are Muslim.

While Muslims in the United States tend mostly to be from Arab countries, Pakistan and South Asia, the Twin Cities area in Minnesota is home to the largest Somali community in the United States. They began arriving there in 1991 when the Somali government collapsed.

“These Muslim youth have similar challenges to any American youth living in an urban area,” Mukhtar said.

There’s high unemployment and a lack of quality youth programs, he said. Many kids in the program don’t finish high school, he said. As Muslims, they have the added burden of stereotyping and stigma.

“It’s critical that all youth workers — communicators, educators, nonprofits — that work with all youth and Muslim youth specifically pay more attention to this demographic,” he said.

Handbook for Muslim teens

After the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, Dilara Hafiz, then living in Arizona, saw a need to address issues facing Muslim young people.

On Sept. 10 that year, her son Imran, then a middle-school student, went to bed an American, she said.

“He woke up a Muslim,” Hafiz said. Although he was born in the United States, he came to be seen not as American, but as “the other,” she said.

Imran was barred from a middle-school pick-up soccer game after 9/11. “You’re in the Taliban,” a boy told him.

“Teenagers are extremely vulnerable to being ‘other-ized,’” Hafiz said.

She and her daughter and son co-wrote “The American Muslim Teenager’s Handbook,” published in 2010, to help kids navigate being a Muslim in the United States.

Her kids have worked to dispel the notion that they’re foreigners.

“The way we dealt with it was to be proud of what you are and speak up,” she said.

Her daughter, Yasmine Hafiz, now an adult, spoke up when a student in her class at school said that the Koran was demeaning to women.

“Actually, Islam gave property rights to women in the seventh century,” Yasmine told the class.

Girls at the Brian Coyle Center, which is part of Pillsbury United Communities in Minneapolis, celebrate a basketball win.

But to speak up, “children have to be knowledgeable and confident enough,” Hafiz said. They have to have a supportive atmosphere.

Having a voice and having support

Every Thursday at the Brian Coyle Center, young people express their feelings and ideas through spoken word in a program known as Teen Voices. A young adult staff member works with the youth, but the program is youth-led.

The kids also take trips to civic events, where they participate in meetings and discussion. They are hoping to make podcasts through a local community radio station.

The kids know there are wrong-headed perceptions about Muslim youth and their Cedar Riverside neighborhood, Mukhtar said. They can change those perceptions by telling their own stories, he said.

“Our youth are so much more than what the media is representing to the American public,” he said.

To serve the kids well, organizations need to hire staff who are passionate about youth, Mukhtar said. Get staff who speak the language and are from the community. Staff are then able to effectively communicate with parents.

They can also focus on the particular needs of kids in their area.

For example, during the school holidays in December, parents in the neighborhood aren’t taking vacations or going away to visit relatives. They have to work, and their kids may be unsupervised. The Brian Coyle Center sponsors the Coyle Cup, a basketball tournament of 10 teams made up of youth in high school and the first two years of college. The tournament draws youth as players and spectators, and gives everyone a safe space in which to spend time.

Relations with police

Mukhtar’s program has also responded to the nationwide issue of police harassment of young people of color.

A three-month summer soccer program for boys and girls ages 6 to 14 enlists police officers as coaches. The goal is to build relationships.

Police and kids get to know each other. The youth get a chance to see the police as people, not just as a uniform and a gun. Officers who might come in contact with a kid in the future won’t see the kid just as a troublemaker but a youth of the community.

One concern of Mukhtar’s is that, while many youth programs serve kids in high school, few programs serve the older youth ages 19 to 24.

“There’s no outlet for them,” he said. No one is thinking about how to create programs for them and engage them, but these young adults are struggling, he said.

In response, two business ventures through the center include older youth.

A coffee bar known as the Triple C Coffee Cart, designed and led by youth ages 14 to 21, sells coffee, sodas and snacks at the Brian Coyle Center. Youth can develop entrepreneurial and business skills through the project. It also builds intergenerational relationships: Kids who play sports and are involved in after-school activities at the neighborhood center come together at the coffee bar with their elders who access the center’s services.

Similarly, the Sisterhood Boutique on Riverside Avenue in Minneapolis was created by young women ages 14 to 23. Open on weekday afternoons, it sells gently used apparel for girls and women, as well as scarves, accessories, jewelry and shoes. The youth who operate it gain business and professional skills, while they provide affordably priced clothing to the community.

Opportunities for youth at the Brian Coyle Center include a business venture involving young women ages 14 to 23. They operate the Sisterhood Boutique on Riverside Avenue in Minneapolis, where they sell clothing and, in the process, gain business and professional skills.

Concerns about extremist recruitment

The Minneapolis-St. Paul area has been a target of extremist recruiters since 2006, when the African terrorist organization al-Shabaab began recruiting youth there, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

Youth programs have been concerned about the appeal of extremism to young people.

“Minnesota has got the biggest population of Somali youth, [in the nation]” said Paul Meunier, executive director of Minnesota Youth Intervention Programs Association.

“Radicalization is “a big problem here,” he said.

Since 2007, as many as 40 people have left to join al-Shabaab in Somalia and ISIS in Syria, according to news reports.

Among those concerned is Mohamed Farah, who grew up in New York and Minneapolis. He and a group of other Somali Americans started an arts initiative involving spoken word, poetry and music to engage the Somali community around the issue.

Farah is now executive director of the youth arts organization Ka Joog, which grew out of the initiative.

In an interview with MinnPost, Farah said youth who became involved with extremist groups are looking for a higher purpose. He described these youth as isolated and unemployed. They’re “at a low point in life,” he told the newspaper.

“We’re trying to engage young people well before al-Shabab or ISIS engages them,” he said. “We’re trying to engage them at a young age. We’re trying to provide them better opportunities.”

Ka Joog also partners with Boy Scouts and 4-H to offer camping and after-school activities.

“Education and art go hand in hand,” Farah told the MinnPost. “So we’re using art to empower individuals, but also we’re using art to teach about the elements of the Somali culture.”