Photos by Julie Sparenberg

Wellness Coordinator Michelle Fortunado, LCSW, PPSC, meets with a student at San Francisco’s Galileo Academy’s school-based health center. Last year, 2.5 million U.S. students received health services at school-based health centers — including mental health services.

School-based health programs are teaming up with youth-development groups to deliver vital ongoing services to one group of vulnerable students: children with mental-health disorders.

Childhood mental illness is surprisingly prevalent, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reporting up to about 20 percent of U.S. children in any given year receive a diagnosis of attention deficit or hyperactivity, depression, anxiety, substance abuse or conduct disorders. According to the U.S. Surgeon General, about 10 percent of youth have what is considered a serious mental illness, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, major depression or bipolar disorder, which interferes with their functioning at home or at school.

That’s “approximately 7.4 million children through age 18 who have some type of serious mental-health disorder,” said Gary Blau, chief of the child, adolescent and family branch of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Yet, the percentage of young people who receive treatment for these problems remains low. “Approximately a third of the youngsters that have an identified disorder receive specialized services,” said Blau. (See sidebar.) “There is a significant need out there,” he said.

Increasingly children’s emotional or behavioral problems are being addressed where they spend so much of their time — at school.

“Schools are a great place for early screening, assessment and identification, which means there can also be early intervention before a problem becomes a crisis,” said Laura Brey, vice president for strategy and knowledge management at the School-Based Health Alliance in Washington, D.C. Services range from crisis intervention, to support groups for grief or alcohol and drug problems and intensive one-on-one treatment.

“We have four kids per period who have a regular standing therapy appointment with one of our staff members, so we see at least 20 students each day,” said Wendy Snider, wellness coordinator at Thurgood Marshall High School, with 475 students in San Francisco.

But according to Snider, schools can’t do it alone. The on-site health center at Thurgood Marshall has four full-time employees but also relies heavily on a dozen community partners such as the Vietnamese Youth Development Center; Child Youth Center, a Chinese-language organization; and Juma Ventures, which helps youth find internships.

“They’re critical,” said Snider. “We have community-based organizations calling us all the time, saying that they’re working with a child who needs help,”

Schools offer easy access

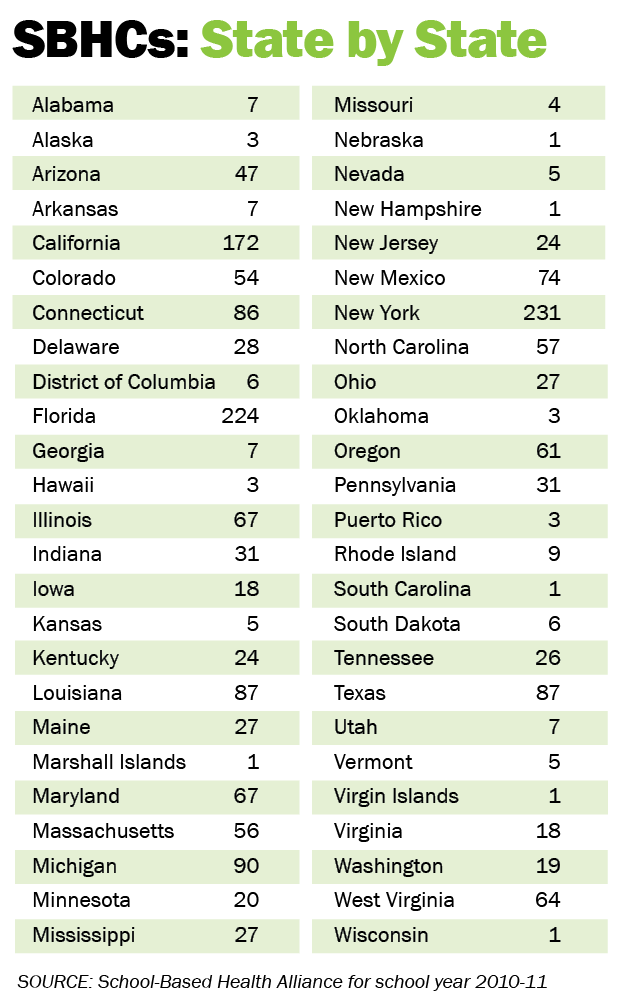

According to the Alliance’s preliminary 2014 census data, 2.5 million students in more than 2,500 K-12 schools nationwide now receive comprehensive health services at on-site primary care clinics known as school-based health centers (SBHC).

More than 70 percent of SBHCs have mental-health staff, so students can see a range of professionals, such as a licensed social worker or counselor, a psychologist and/or a child psychiatrist if they need to be prescribed medication.

School-based health care offers easy access to a familiar setting. According to the 2010-11 Census Report of School-Based Health Centers, the vast majority of SBHCs operate in the school building or on school grounds. They are typically open five days per week. Sixty percent are open before school, and nearly three-quarters are open after school. More than half are located in urban districts, and nearly 70 percent of students are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.

Schools can also provide specialized services, including crisis intervention or peer mediation. “Some of the interventions are done in small psycho-educational groups, which a lot of the time a traditional mental-health provider cannot offer,” said Brey. For example, at Thurgood Marshall High School, a counselor from a domestic-violence support organization comes weekly to talk about healthy relationships and work with students who have witnessed violence at home.

Year-round services

Most SBHCs are sponsored by a larger entity such as a hospital, a federally qualified health center, a public-health department or a mental-health agency. Since they are run separately from the school — often with a separate entrance — they can offer uninterrupted services year-round. “When I ran SBHCs, we remained open all summer long,” said Blau, a former SBHC manager. “We continued with prevention groups, we continued to seek and obtain services across the physical and behavioral-health side, and we didn’t miss a beat.”

Galileo Academy students participate in a workshop on the impact of social media led by Naomi Forsberg, the wellness center’s community health outreach worker.

On-site SBHCs are usually open for summer school, and according to Blau, even if the center closes for a time, young people who need ongoing services continue to receive them at the hospital or mental-health agency that sponsors the SBHC. “If it’s a serious disorder, they wouldn’t just stop treatment,” said Blau. “They would make sure that there were other referrals, that there was follow-up.”

SBHCs are financed through a variety of mechanisms: Medicaid, managed care or private health insurance plans, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program and foundation grants. School districts often provide in-kind support in the form of free space, utilities and custodial services.

The SBHC movement is growing, with preliminary data indicating about 500 new centers have opened since the Alliance’s last census three years ago. Yet, they only serve a small fraction of the nation’s students.

Mental health partnerships

Mental health service “occurs in lots and lots of schools that don’t have SBHCs,” said Sharon Stephan, Ph.D., co-director of the National Center for School Mental Health at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

According to a national survey co-sponsored with SAMHSA, the Center determined that two-thirds of U.S. schools have some contract or relationship with a community mental-health partner to provide comprehensive services. “SBHCs are a fantastic model, but they are only a small part of that picture,” said Stephan.

For example, Stephan said, in more than half of Baltimore public schools, a community mental-health clinician has an office in the school and is responsible for a full array of services — from teacher education to targeted treatment for students with issues like depression or trauma.

Dr. Jeff Bostic is the director of school psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital and a psychiatry consultant to about 60 school districts in New England. “I’ll go into a school every Monday or Wednesday for several hours and meet with the counselor, and she’ll have a child who is depressed, or suicidal or traumatized, and I’ll try to figure out what the child needs and how to provide that,” said Bostic.

Comprehensive school mental-health programs typically serve students year-round. There’s no universal model, but even if summer activities are curtailed, a student in ongoing treatment might receive some combination of home visits for therapy as well as site visits at the community mental-health center to see a psychiatrist.

According to Stephan, funding for comprehensive school mental-health programs differs across the country. Programs often rely on blended funding, with contributions coming from the school system, local or state mental-health authorities, grant and foundation funds, as well as third-party reimbursement.

Whether it’s in a stand-alone clinic or through a community partnership, schools and after-school programs have come to play the major role in providing treatment for children’s emotional and behavioral problems. A 2000 study in the journal Clinical Child and Family Psychology found that of the children who receive treatment, 70 percent of them get services at school.

Whether through direct services or referrals, youth development organizations play a critical role in making sure troubled children get the care they need. “We couldn’t do it without help from our community partners,” said school wellness coordinator Wendy Snider. “They’re in the neighborhoods, working with the families already, so we make a natural team.”

Elaine Korry is a freelance print and public radio reporter based in the San Francisco Bay Area.

See sidebar “Child Mental Illness Widespread, yet Untreated”