Worker's Justice Project

Members of the Worker’s Justice Project speak at a human rights conference, with Isabel Castillo in the middle.

NEW YORK — The women wait on an exposed street corner above the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway at the intersection of Marcy and Division avenues. Wind blows trash against the fence behind them.

They stand in small groups, mostly speaking Spanish. Some sit on the railings with their hoods up, huddled against the cold. Hasidic Jews from the surrounding neighborhood of Williamsburg pass by speaking Yiddish. It’s early on a Sunday morning, the first day of the workweek in this community.

The women are hoping to be hired to do housecleaning.

Hasidic Jews have more children than most Americans (Williamsburg’s median age is 19, while the city’s is 35, according to the 2010 census) and don’t have time to clean, said Yadira Sanchez of the Worker’s Justice Project, an advocacy group.

Many of the women on the corner are single mothers, and most have children, she said. While the women are able to help support their families by picking up work on the corner, caring for their children is a daily struggle.

Day laborers don’t qualify for New York City day care services because the city requires documents from employers. Paying for daycare or babysitters is expensive.

“The majority of immigrants are coming here to work and improve their lives,” Sanchez said. “People cannot do it because they don’t have access to the sources they need in order for them to continue improving.”

Some mornings up to 70 women wait on the corner, she said. “We have people from Ecuador, Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Central America, South America,” she said. “We also have Eastern Europeans like Polish, Ukrainians, Croatians.”

Day laborer pool in the thousands

The number of day laborers in New York City is impossible to know, said Hector Cordero-Guzman, a professor at Baruch College who studies the issue. It is extremely complicated to measure the population, but he estimates that on a given day there are about 2,000 to 3,000 day laborers active in the city, and about 5,000 to 10,000 workers in the day laborer market.

He guesses 10 to 20 percent are women, although women are less likely to congregate on corners and may be underrepresented.

“It’s a population that’s not a fixed, stable population that’s easy to count,” said Cordero-Guzman. “It’s not like how many people live in your house. It grows and shrinks.”

Many of the women come to the Williamsburg corner from other neighborhoods for the work, said Isabel Castillo, 40, who has done so for a year and a half. She migrated to the U.S. from Ecuador six years ago. She is divorced with two sons, a 6-year-old and a 19-year-old.

Castillo said she moved to improve her financial situation but has not been able to do so and that about 70 percent of the women on the corner are in the same situation.

The work is not all bad for the women, Sanchez said. They have some flexibility, which allows them to pass up work if they need to take care of their children. If they have a steady employer in the neighborhood, their friends on the corner can cover for them if their child is ill.

“I’m not saying the community they’re working for is bad,” Sanchez said. “What I’m trying to say is that the laws are not protecting domestic workers.”

Castillo has been a day laborer for six years and previously worked in Manhattan, Queens and Long Island. She used to find jobs through word-of-mouth, she said, and had a more personable relationship with her employers.

Language barrier, uncertainty

Williamsburg residents meet and negotiate with the women at the corner, then bring them to their homes. Not all the women get work, however, and the employers are often unclear about how long they want the women to work for. The uncertainty makes it difficult for the women to make arrangements for their children, Castillo said.

“That is a problem,” she said. “Sometimes I don’t get a job for that day, but we need to pay the babysitter.”

The language barrier is also a problem. Most Hasidic Jews speak English as a second language and do not speak Spanish, and most of the women cannot speak English well, Sanchez said.

“They cannot explain why they need to use a mop, why they need to leave early,” she said. “Not because they want to leave the work, but sometimes because they need to go back and pick up their children.”

Day care costs $500 a month, Castillo said. She put her 6-year-old in a program but started finding bruises on his arms. The children were fighting and she thought staff was not taking care of them. She now pays a babysitter $25 a day. She usually makes about $40 a day, she says, and needs to pay for transportation.

To receive subsidized child care, the city requires proof of citizenship, a Social Security number and either pay stubs or a referral from an employer.

“They ask for a letter from the employer stating that the person is working with them for about 40 hours,” says Sanchez. “And they’re not able to provide it because they don’t have a steady employer.”

The women usually work every day but Sunday. On Castillo’s days off she sees her family but needs to do laundry, shop for food and clean, she said.

Lack of health care

After work, the women often come home sick from exposure to cleaning chemicals, like Tilex and Lysol. They do not have access to a bathroom while waiting on the corner, and do not want to leave because they could miss a potential employer.

Many get urinary tract infections, Sanchez said. During the winter they worry about the flu.

A $30 flu shot is hard to pay for, Castillo said. They often cannot afford proper treatment, for themselves or for their children.

“When the ladies are sick they drink home remedies,” she said. “Tea, Tylenol or Motrin. That’s it.”

Castillo’s 6-year-old has insurance but her older son doesn’t. Paying for medical treatment is a constant worry.

“All the time I say to my big son, please be careful with the money,” Castillo said. “Watch the teeth, everything. If I go to the dentist, maybe it’s $100, it’s a lot of money.”

Her work situation is also hard for her younger son. He is in the first grade and learning to write. He writes her letters from class telling her he wants her home, she said.

Worker’s Justice Project

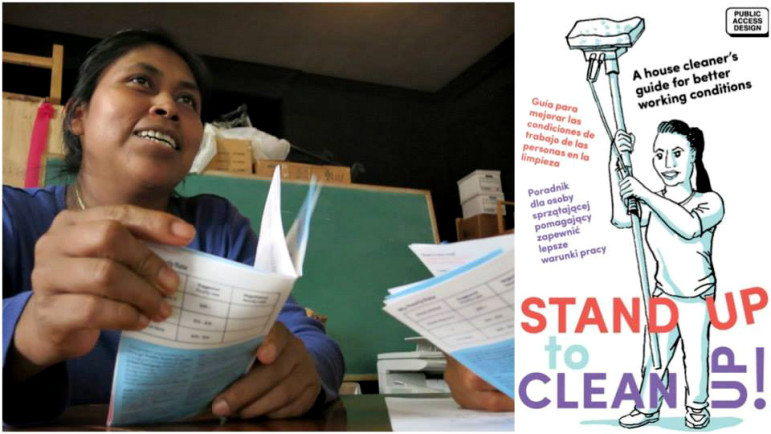

An illustrated translation guide released by the Worker’s Justice Project.

Some of the women from the corner are taking their situation into their own hands. Some belong to the Apple Eco-Cleaning Co-op, a house cleaning cooperative that uses only nontoxic products. The co-op also provides job training for the women.

In November, the Worker’s Justice Project released an illustrated translation guide for cleaners with phrases like “I cannot mix two cleaners because it is dangerous” in Spanish and Polish. The women also recently partnered with Jews for Racial & Economic Justice, an advocacy group that has worked with domestic workers since 2002.

“This is going to be the first time we are going to work in deep partnership with a women’s group,” said Rachel McCullough, a community organizer for the group. “We don’t know yet what it’s going to look like.”

Sanchez believes that organization is the way forward. The Worker’s Justice Project aims to use education, workshops and economic alternatives to improve day laborers’ working conditions and wages, she said.

“Even if they don’t have any legal status they can still have rights, human rights, and workers’ rights,” she said. “I want people to know that.”