From The Chicago Bureau:

From The Chicago Bureau:

CHICAGO — Like many young children, Nancy Floy spent much of her time at a daycare while she was growing up–but her childhood was anything but normal.

When Floy was four, a particularly rough john shattered her pelvis, setting off a chain of events that led to the pimps’ arrest and the closure of the trafficking daycare.

Floy testified against her father and the other pimps, who were imprisoned. The exploitation resumed when Floy’s father got out of prison, though, and continued for more than two decades.

“I think the last time I engaged in prostitution was when I was maybe 30, so it’s only been 26 years, and even now, when I get worried about money, my mind will still go there,” Floy said. “ It’s hard, when you’re an adult, to not fall back into it, because it’s familiar, it’s what you know, it’s what you’ve been told, because you’ve been beaten down and told that you’re a hooker and a whore.”

Floy’s story is not an uncommon one. Many survivors begin engaging in prostitution at a young age– according to a 2010 US Department of Justice report, the average age is 13-14 years old. By law, children under age 17 cannot consent to prostitution, according to Andrea Krauth, an analyst with the FBI’s civil rights division in Chicago.

The effects of being trafficked at a young age are particularly horrific, Floy said.

“When you’re a kid, the whole thing is absolutely soul-crushing,” she noted. “It changes your brain chemistry, your nervous system, you are never the same. You’re robbed of a childhood.”

Though there is no unifying characteristic of a trafficking victim, people who are poor, undocumented, or underage are particularly vulnerable, said Darci Jenkins, the Midwest regional services coordinator for Heartland Alliance, a Midwest-based anti-poverty organization that works with victims of sex and labor trafficking.

“The traffickers are preying upon those who aren’t documented, because those victims who aren’t documented aren’t going to run to the police,” Jenkins said. “Traffickers would use that to hang over their victims heads, and would say if you go to police, if you ask for help, if you run away, you’re just going to be deported.”

The findings of a 2005 report conducted by The American Immigration Law Foundation back Jenkins’ statement.

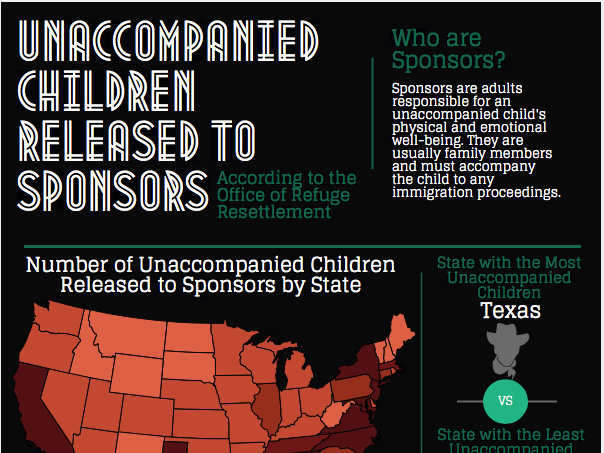

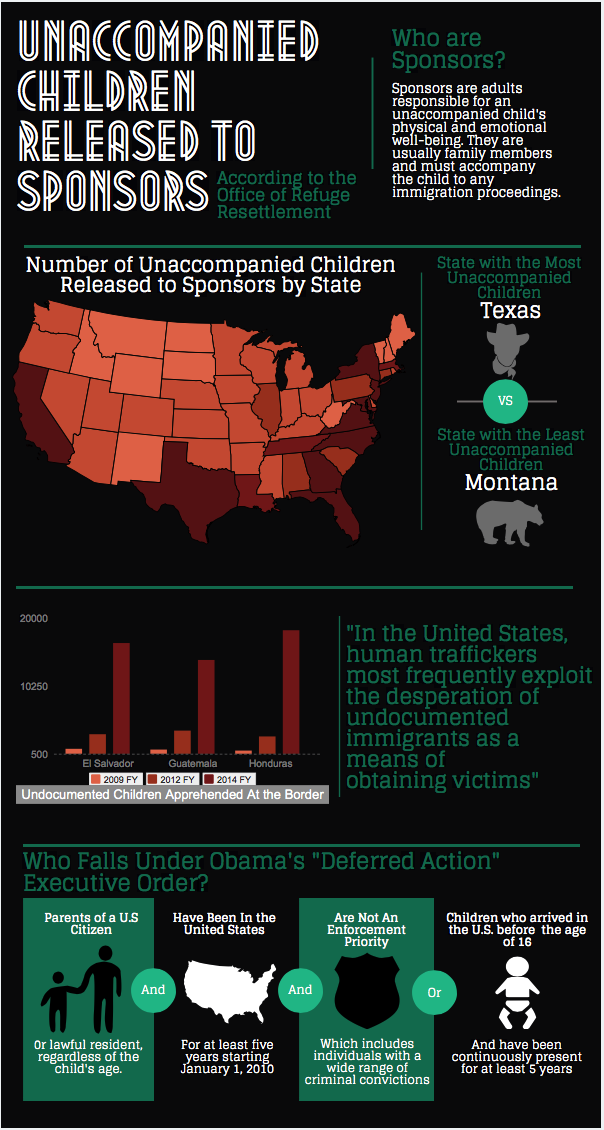

According to the report, “In the United States, human traffickers most frequently exploit the desperation of undocumented immigrants as a means of obtaining victims.”

Due to drug and gang related activity in countries such as Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, these undocumented immigrant children have been entering the United States by the tens of thousands in an attempt to avoid violence, causing an unprecedented influx of children who are at high risk for exploitation.

President Barack Obama addressed this issue with an executive order November 21st. The order will grant “deferred action” to parents of United States citizens or legal permanent residents who have been in the country for five years and young people who were brought into the country illegally as of 2010, granting three years of protection to those who qualify.

In 2005, the FBI designated Chicago as one of 13 locations of “High Intensity Child Prostitution.”

Illinois has the sixth-highest call volume into the National Human Trafficking Resource Center’s hotline following California, Texas, Florida, New York and international locations, with 348 calls in 2013.

The hotline is a resource for victims and community members to report incidents of human trafficking run by the Polaris Project, an organization that strives to eradicate human trafficking and works with survivors. The hotline averaged more than 2,600 calls per month about child trafficking victims that had moderate- to high-risk indicators of child trafficking in 2013.

Chicago’s problem has prompted organizations to take action, raising awareness for trafficking and providing services for the victims.

The International Gender Equality Movement, a chapter of the United Nations’ GirlUp campaign at Northwestern University, is co-sponsoring a panel on human trafficking this Wednesday to educate the university’s students about commercial sexual exploitation in the area.

“I think when people think of sex trafficking and other human rights violations, they think it’s happing very far away,” said iGEM co-founder Carly Pablos. “It definitely involves a lot of women and girls all over the world, but also just a huge number here in Chicago, and no one’s really talking about it.”

While preventing the commercial sexual exploitation of children has a history of strong bipartisan support, the massive increase in trafficked children this year is calling into question the efficacy of the extensive safeguards to protect undocumented minors who are found by the government.

As a result, previous legislation designed to protect child victims of trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation is now coming under scrutiny, with lawmakers considering cutting or altering some of the law’s protections to ease the strain on resources presented by this influx.

The William Wilberforce Law, also known as the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008, gave the federal government’s the most comprehensive human trafficking law while making a number of changes, several of which focused on child victims and suspected victims.

The portions of the 2008 law contested due to the increase of unaccompanied minors, sections 212 and 235, added protections for unaccompanied children crossing the U.S. border.

The passage of the Homeland Security Act of 2002 transferred responsibilities for the care and placement of unaccompanied children from the Commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service to the Director of the Office of Refugee Resettlement – responsibilities that were expanded by the Wilberforce law to include more protections for children suspected of being trafficking victims.

Since then, ORR has cared for more than 150,000 children nationwide, with 57,496 of them referred in just the last year.

ORR provides care including foster care, group homes, shelter and residential treatment centers. The care providers, more than 100 nationwide, operate under cooperative agreements and contracts, and provide children with classroom education, health care, socialization and recreation, vocational training, mental health services, family reunification, access to legal services and case management. Illinois houses nine ORR-supported shelters.

In August 2010, then-Gov. Pat Quinn signed the Illinois Safe Children’s Act into law. The law was modeled after the 2008 William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act.

The Illinois Safe Children’s Act transfers jurisdiction over children arrested for prostitution to the Department of Human Services, rather than the criminal system, through which they were previously processed, allowing them to get the services afforded to victims instead of being treated as suspected criminals.

A 2010 report by the U.S. Department of Justice found that 300,000 children are at risk of being prostituted within the United States. Under the William Wilberforce law, all those under the age of 18 who are arrested for prostitution are immediately classified as victims and treated as such.

“Many people consider the sex trafficking of children to be an international issue and not a problem that impacts us here right in our own communities, but that is not the case at all,” said Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez in a statement about the Illinois Safe Children’s Act’s passage.

This law added an extra step to protect potential child trafficking victims, with the intention of ensuring that children were not being sent back into an exploitative environment.

However, the law was enacted when less than 10,000 children were crossing the border each year, while nearly 60,000 are expected to have entered the U.S. by the end of this year, according to a June Al-Jazeera report.

This leaves lawmakers trying to balance the strain on resources presented by this massive number of children who are in need of financial and medical support.

Although this is a national issue, the work of preventing commercial sexual exploitation of minors has strong roots in both Chicago and the surrounding suburbs, where hundreds of these minors have landed, according to Katherine Kaufka Walts, director of the Center for the Human Rights of Children at Loyola University Chicago.

One cause of Chicago’s trafficking problem is O’Hare International Airport. Often ranked the world’s busiest airport, it is considered a highly used transit location by traffickers to transport victims and then disperse them among other cities and states as needed because of its strategic location, according to a University of Illinois human trafficking fact sheet.

In metropolitan Chicago, 16,000 to 25,000 women and girls are involved in commercial sex trade annually, with one third of them first getting involved in prostitution by the age of 15, and 62 percent by the age of 18, according to a 2008 report by researchers from DePaul University and the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority.

Andrea Krauth of the FBI said her division, in an effort to “get the word out,” works within the Chicago area and gives presentations to community members discussing human trafficking, with special attention paid to crimes against children.

Krauth gave one of these presentations in the North Side Chicago neighborhood of Edgewater last fall, where she discussed indicators of trafficking and resources for victims and other community members to report incidents of suspected trafficking.

“We went to Edgewater because of the large immigrant population—30 percent of the population is foreign born,” Krauth said.

Illinois State Senator Heather Steans (D-Chicago, 7th District) sees the value in educating the Chicago-area population about the dangers and legislature surrounding human trafficking.

“It’s very important to bring this information to a public forum and to get the information out there, especially the hotlines,” said Cathy Smith, spokeswoman for Steans.

In addition to the FBI’s civil rights division in Chicago, there are several organizations in the Chicago area such as Chicago Alliance Against Sexual Exploitation, that work directly with victims and survivors of human trafficking, including minors.

Caleb Probst, an educator with CAASE, attempts to prevent human trafficking before it begins by going into high schools in the Chicago area and talking to students about the issues of commercial sexual exploitation and domestic sex trafficking.

His mission to change the culture that supports the demand for cultural exploitation.

“It’s not that we think any high school student is actually engaged in the purchase of people for sex,” Probst said. “But we like to talk about these attitudes before they lead to a problem.”

The preventative education Probst provides can help to lessen the demand side, hopefully decreasing the chance newly immigrated children will face commercial exploitation in Chicago.

For those who already have, though, organizations like Heartland provide services to help them move forward.

“[Other people] think they’re broken,” Jenkins said. “They think they’re weak, they need support, they need long-term support, but we just show them the way for a little while until they can get back up on their feet, to have their own income, and get on with their lives.”

To end trafficking, said Floy, lawmakers and activists need to take a two-pronged approach: First, go after the johns and end the demand, as Probst and CAASE are working to do; and second, offer victims an alternative.

“All we’re looking for is family, that’s what it becomes–the pimps become your parents, and the other kids, that’s your family,” Floy said. “That’s all we want, is family. We want someone to love us and care for us–if we were offered that, and not to have to have sex with people, oh my God, we’d take it in a heartbeat.”

Katharine Currault and Lauren Myers contributed to this report.

This story was produced by the Chicago Bureau.