Contentious, dysfunctional, divisive and ineffective. Perpetual paralysis. An undercurrent of mistrust and conflict. A theme…of doubt and lack of confidence.

Those harsh words sound like a description of the notoriously partisan U.S. Congress. They are actually aimed at a more local source of frustration — school board members who meddle in hiring and firing, who misspend precious dollars, who disrupt board meetings or even hurl insults. But there’s a critical difference: When school boards misbehave, a private, nonprofit group has the power to rein them in.

Those harsh words sound like a description of the notoriously partisan U.S. Congress. They are actually aimed at a more local source of frustration — school board members who meddle in hiring and firing, who misspend precious dollars, who disrupt board meetings or even hurl insults. But there’s a critical difference: When school boards misbehave, a private, nonprofit group has the power to rein them in.

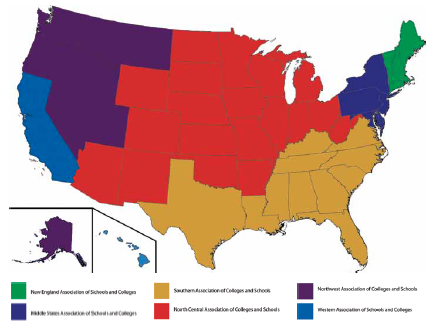

AdvancED, parent company of three of the nation’s six regional agencies that accredit schools, sets standards for 1,300 school districts and 23,000 schools in 37 states, giving it a dominant influence over U.S. education. Some say its role has become too dominant.

Accreditation is a stamp of approval sought by schools around the world — from county- or city-wide school systems, to juvenile justice education programs, to exclusive private schools. The accrediting agencies look at school leadership because if a governing board is mired in controversy or conflict, students, employees, and the whole community can suffer. Still, if elected school boards need to be straightened out, should that happen through a private process run by professional educators? Or through public debate and the ballot box?

The path through political chaos has significant consequences. School board turmoil affects how well the schools are run, and a downgrade in accreditation mars the reputation of the school system. And, some critics say, giving too much power to a private organization erodes a small slice of democracy.

“Democracy is hardball. It’s rough, it’s raucous. It always has been in the history of our country,” said Don McAdams, a former Houston school board member who founded the Center for Reform of School Systems to help improve school board governance. “So here’s a private organization involving itself, really, in the democratic process. And the democratic process is something that has to be regulated by the people themselves.”

Complaints trigger scrutiny

Ground zero for this debate lies just south of Atlanta in Clayton County, Ga. In 2008, Clayton County became the first system in 40 years to lose accreditation from the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS) after its board became mired in infighting. SACS has since downgraded the accreditation status of 16 other districts in Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina related to governance problems, though none have lost accreditation.

All of those cases involved mismanagement, micromanagement, ethical lapses or financial wrongdoing on the part of school boards. The accrediting agency sometimes was able to influence board members to change their ways. Some board members resigned. Others were removed by the governor or defeated in election.

SACS played the heavyweight. AdvancED now receives hundreds of complaints each year from parents, teachers, administrators, school board members, community activists and even superintendents seeking to influence change.

“Who do you go to [when you want] to fix what seems like an unfixable situation?” said Trisha Powell Crain, a self-styled watchdog over the Birmingham City Schools, which have been taken over by the state of Alabama. Crain once complained to SACS that the Hoover city school board in suburban Birmingham was micromanaging, although as a parent, she didn’t really want to jeopardize the system’s accreditation. She simply wanted SACS’ stabilizing influence.

Local chambers of commerce or parent groups have tried to exert a similar influence by rallying for or against school board members in an election. But in many communities, school board elections are held in the spring or summer, when only a tiny percentage of people vote, said Mark Elgart, president and CEO of AdvancED, which is based in Alpharetta, Ga. If communities want to take control of their school boards, they need to start with the election process itself, he said.

“I don’t think democracy is truly being supported. Because if we were truly committed to a democratic process, we would optimize the opportunity for voters to exercise their democratic right to vote during [November] when they normally vote,” Elgart said.

Monopoly or monitor?

Schools voluntarily seek accreditation, but they often need that seal of approval to show that they meet a set of common standards. In some cases, students from non-accredited high schools have to meet a higher bar for college admissions or scholarships.

The nation’s six regional accrediting bodies approach their task somewhat differently. The Southern association has a history of taking a tough stand on school governance — and of stepping into political controversies.

Even years before the civil rights movement, SACS punished schools for racially-charged political interference. In 1941, SACS revoked the accreditation of all Georgia state-supported colleges for whites when then-Gov. Eugene Talmadge used his political muscle to replace members of the Board of Regents. Talmadge wanted the board to fire the University of Georgia dean of the college of education, who had dared to point out the disparities between the education of blacks and whites in Georgia. Talmadge lost reelection, and SACS restored accreditation two years later.

In 1962, SACS took a central role as Southern schools faced desegregation orders. SACS considered revoking the accreditation of the University of Mississippi when then-Gov. Ross Barnett tried to bar James Meredith from integrating the campus. As segregationists protested Meredith’s enrollment and a deadly riot erupted, federal marshals were called in to protect Meredith. SACS eventually decided to put the university under “extraordinary status” so it could monitor the situation and ensure academic freedom and independence from outside political pressure.

The controversies today that involve SACS are minor in comparison, but the accrediting body’s actions still provoke some backlash. Amid one recent political dispute, a North Carolina school board member called SACS and its parent, AdvancED, “a totalitarian monopoly from Atlanta.”

In contrast, other accrediting organizations take a more restrained approach. The North Central Association of Colleges and Schools, also a part of AdvancED, has only placed two school systems on “warned” status in the past four years for governance and other issues.

The New England Association of Schools and Colleges, which accredits schools and not school systems, doesn’t get involved in school board governance. David Brown, executive director of the Western Association of Schools and Colleges Accrediting Commission for Schools, asserts that while schools in California and Hawaii can lose accreditation because of the bad behavior of boards, “it has become less frequent than in the past.”

To AdvancED’s Mark Elgart, governance and leadership are central to the accreditation standards. “We have the best vehicle to hold schools and systems accountable for performance – better than a state government, better than the federal government – because we’re in the schools more often. We know more about them,” Elgart said.

In fact, accreditors should be even tougher than they are, he asserted. “Most of the accreditation community does not apply their requirements with rigor. If they were applied with rigor we would have this [accreditation action] happen more frequently,” Elgart said.

Step up or step down

In January 2011, Mark Elgart stood before the Atlanta Board of Education with a plea: “You believe that some of this is about politics. It’s not about politics for us…This is about 47,000 kids.

“And what we know about school boards and their effectiveness is that when they focus their decisions on the children they serve, they make far better decisions than when they focus on their own individual politics and agendas. I ask you, on behalf of this community, that you put aside those politics. Because right now, 47,000 kids need you to lead.”

For the first time in months, board members left a meeting in complete agreement. They wanted to save the system from the shame of losing accreditation.

Board members had been split 5 to 4, and one faction had sued the other over who would serve as board chair and vice chair. Meanwhile, Atlanta Public Schools were reeling over a cheating scandal that ultimately implicated 178 educators. Superintendent Beverly Hall retired, and soon after, the board chairman Khaatim Sherrer El resigned and left the city for a job in Newark, N.J.

Throughout the turmoil, a parent group called “Step Up or Step Down” put pressure on the board to comply with the SACS requirements. School board members and parents had asked SACS to intervene, essentially inviting them to scrutinize the system’s accreditation.

In November 2011, after the APS board worked with a mediator and held town hall meetings to regain public trust, SACS took the Atlanta Public Schools off probation and moved them to “accreditation on advisement.” APS regained full accreditation a year later.

“I don’t know without the SACS oversight whether this board would have voluntarily gone through mediation or a lot of the hard policy work that needed to be done,” said Julie Salisbury, one of the founders of Step Up or Step Down. “I really think that has been the prescription for healing.”

A split on party lines

In Wake County, N.C., which encompasses Raleigh and surrounding communities, SACS waded directly into a political battle. The central argument: Should students be bused to even out the socioeconomic profile of the schools, or should they be able to choose from neighborhood schools?

The controversy began when a Republican majority was elected to the school board (even though the board is ostensibly non partisan). They brought in a new superintendent and voted in the “choice” plan.

“They went about the business of changing school policy as if they were driving a steamroller,” explained Jacob Vigbor, professor of public policy and economics at Duke University. “They did their best to minimize community comment at school board meetings. They tried to act dictatorially.”

To Vigbor, the split went beyond partisan politics and reflected the different perspectives of long-time residents who liked the status quo (the Democrats) and relative newcomers who favored neighborhood schools (the Republicans).

The NAACP saw it literally in black and white – as a move toward resegregation – and filed a complaint with SACS.

SACS put the district on a warning status, and in November 2011, Democrats again gained a majority on the board. The schools gained a slightly higher status of “accredited on advisement” when a SACS team found a “greater sense of [public] confidence” in the board.

Then the new majority began changing the student assignment plan and fired the superintendent on a 5-4 vote behind closed doors. The Wake County Taxpayers Association filed a 110-page complaint with SACS.

Elgart says SACS has a role to play in guiding Wake County’s school board back to stable governance: “In Wake County, I think we are, right now, the objective, independent agency saying ‘You don’t have it right yet, folks. You have a very good school system that has now gone through a period of chaos because you’ve gone from governing the system to legislating it. And you’re not through this yet. …You need to get back to governing the system in the best interest of families and students and not legislate it in the best interests of politics.’”

In October 2012, the Democrats and Republicans on Wake County’s school board actually agreed to make incremental changes in the student assignment plan.

States decide accreditation power

The power of accreditation lies in its value as a mark of quality. School systems seeking accreditation from AdvancED pay annual dues of $650 per school and expenses related to site visits. For large school systems, that can total tens of thousands of dollars each year. DeKalb County Schools, an Atlanta-area system, budgeted $105,000 in 2011-2012 just for travel expenses for the SACS review team. Systems also devote staff time to conduct a self-assessment. They undergo a thorough review and generally must show improvement toward a set of goals.

But the force of accreditation varies by state. For example, the University of California collegiate system requires its applicants to come from regionally accredited schools, although it offers an alternate path to admission based on SAT and ACT scores. Georgia’s HOPE scholarship requires students to attend an accredited high school, although students from non-accredited schools can still qualify for the scholarship if they are at or above the 85th percentile on the SAT or ACT. In Florida, student athletes must come from an accredited school, or from a non-accredited school that regains its accreditation within three years.

North Carolina recently took a stand to limit SACS’ power. A 2011 law prohibits North Carolina colleges and universities from considering accreditation in admissions, scholarships or loans, and empowers the state Board of Education to accredit schools.

We’ve taken away their monopoly stature in North Carolina,” said Rep. Hugh Blackwell (R-Burke), a bill sponsor who served on the Burke County school board from 1987 to 1995. SACS placed Burke County Schools on probation in 2009 because of “turmoil and chaos” on the board, according to a SACS report. Their standing improved to “accredited on advisement” in 2012. Blackwell was especially upset with SACS intervention because Burke County schools had higher student performance than many other districts in the state.

Conversely, Georgia has given accrediting agencies unprecedented power. A school system’s drop in accreditation status to “probation” triggers a hearing before the state Board of Education and the possible removal of board members by the governor.

SACS has placed 10 Georgia districts on probation because of school board dysfunction since 2008, when Clayton County lost its accreditation. Then-Gov. Sonny Perdue removed four Clayton school board members, and five others left the board.

Elgart stresses that AdvancED did not seek the power to provoke the removal of board members.

Nonetheless, Elgart holds up the Georgia law as a model. “You talk to state [school] chiefs across the country and they will tell you they would like to have the ability to intervene when [school board] matters become a problem,” he said.

Is there gain after the pain?

You can’t blame parents in Clayton County for being upset, as they were at a recent board meeting. SACS sent a “letter of concern” just a little more than a year after the county finally regained full accreditation.

“Now, it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see that something is wrong here,” one mother railed at the school board. “Do us a favor. Resign, because if you don’t resign, we are going to take steps to help you make your decision.”

There’s an ugly history here. In 2003, board bickering caused the district to be placed on accreditation probation. When the county lost accreditation in 2008, enrollment dropped by about 3,400 students as families moved out of the county or into private schools.

The county’s shame of being the first school to lose SACS accreditation in 40 years was plastered in the New York Times, the local evening news, online blogs and a myriad of daily newspapers. The accreditation action was blamed for worsening the sharp drop in housing values that came with the recession.

If getting tough on accreditation improves school governance, then why isn’t Clayton in better shape?

“The players may change, but the culture of the county and the culture of the school system is still very similar. That’s of deep concern to us,” Elgart explained.

He described it as “a culture where there is a lack of authentic focus and effort to help every child succeed.” Where the adults in their individual interest are paramount over kids and where the community doesn’t have a vision to move forward — a community constantly debating its past and present rather than creating its future.

“It’s actually more than the board and the superintendent. It’s the community. It’s the civic leaders, it’s the business leaders. It’s the school leaders. It’s a community issue. That’s why it’s larger than just the accreditation of schools. The culture of the community needs to be transformed,” he said.

Pamela Adamson, the beleaguered chairperson of the Clayton County school board, argues that even with its conflicts, this board is far from the dysfunctional mess of 2008. The schools have begun to stabilize, and enrollment has rebounded.

Adamson said she hopes SACS recognizes the improvements. As to lingering problems on the board, she noted: “I’m a great believer in the democratic process. Legally, that’s about the only course we have right now.”

Michele Cohen Marill is an Atlanta-based freelance writer specializing in health and education issues. She has written for Good Housekeeping, Parents, WebMD Magazine and other publications and is a contributing editor of Atlanta magazine.