FARMVILLE, Va. — Parents here are literally begging the Prince Edward County supervisors to increase property taxes next year to make up a $2 million shortfall in the public school budget and prevent teacher layoffs. But none of them are surprised that the supervisors have said no.

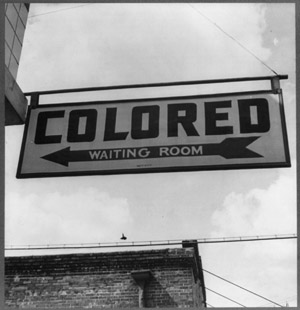

Over the past 60 years, this county government has been notoriously cheap, especially when it comes to paying for public education. In fact, the supervisors’ opposition to higher property tax rates has proven to be the most enduring remnant of the old Jim Crow era. This is, after all, the only local jurisdiction in the United States that actually abolished public education for five years – between 1959 and 1964 – to delay racial integration of the schools.

Dozens of parents and teachers showed up at the supervisors’ meeting on April 17 in what they already knew would be a futile effort to change the county’s reputation.

Dozens of parents and teachers showed up at the supervisors’ meeting on April 17 in what they already knew would be a futile effort to change the county’s reputation.

“This is becoming an ‘us-against-them’ community again,” Barbara Arieti, a school counselor, warned the supervisors. “I don’t know why you can’t grasp the concept of ‘we.’ ”

The Rev. Samuel Trent, also a parent, reminded the supervisors that “Prince Edward is a school that nobody wants to send their children to.”

Not one person spoke out against an increase in property taxes. Carolyn DeWolfe, whose grown children were educated in the local public schools during the 1970s, said that pleading with the supervisors for more money for public education has often been considered “a rite of spring” in this rural south-central Virginia community. Parents’ and teachers’ efforts in the past two years have been based on the need to make dramatic improvements at the high school, which in 2010 was officially designated as one of the lowest-performing schools in Virginia.

Meeting to discuss the budget again one week after hearing the testimony of teachers and parents, the supervisors explained that they were against a tax hike because many local taxpayers could not afford to pay it. Vice Chairman Howard Simpson said the schools always have had the funds “that the board thought they have to have.”

The beginning

The long-term stalemate over education spending here had its beginning a century ago, when local white supremacists argued there was no point in spending money on classes for African-American children because they would only end up going to work in the fields. And it continues today, primarily because of the prominent role still played by the local private school that was created in the late 1950s with public money to educate the children of the town’s white elite. The hatred engendered by this constant reminder of the county’s dark past is, as one school official described it, “the ugly reality that is always just below the surface.”

The story of Prince Edward County Public Schools demonstrates how the unresolved racial issues of the 1950s and 1960s are at the root of today’s achievement gap between black and white children in our nation’s schools. For the past three years, the county schools have failed to meet the standards set by the No Child Left Behind law. In 2008-09, some 95 percent of the white children passed the English portion of the state test, known as Standards of Learning, while only 79 percent of black students did. A comparison of results on the math test was 89 percent for white children, 66 percent for blacks. Many educators believe that closing the gap between racial outcomes in schools across the country should be the most important civil rights objective in this decade.

Prince Edward County has the third-lowest property tax rate in the state: 42 cents on every $100 of assessed value. That compares to $1.09 in Fairfax County, Va., outside Washington, D.C. As a result of the county’s long history of neglecting funding for public education, more than 20 percent of Prince Edward’s adults – mostly African-Americans – do not have high school diplomas.

The county board’s historical willingness to settle for low-performing schools has slowed economic growth and created a permanent black underclass in this once prosperous tobacco-growing community. The policy has succeeded in shrinking the property tax base in Prince Edward County, as well as the public school enrollment. Heather Edwards, a parent of two students and a French teacher at Longwood College, in her presentation to the board, noted that many people who work in Prince Edward County have chosen to buy houses in one of the surrounding counties where the schools are known to be better.

“These families would be happy to pay a higher tax rate … would own real estate in the county, they would buy goods and services in our county, would be leaders in our community, if only they felt this community were one that values education,” she said.

Prince Edward’s role in history

While Prince Edward County’s history of racial turmoil is not as well-known as that of Philadelphia, Miss., or Birmingham, Ala., it played a very important role in the civil rights era of the 20th century. In the early 1950s, Prince Edward’s segregated black high school was so overcrowded that many students were taught inside flimsy tarpaper shacks erected in the school yard. The white community and the county’s black parents were shocked when the black high school students staged a strike in 1951 to protest the overcrowding of their school. Adult African-American residents, who were always treated as lesser beings by the white establishment, would not have had the nerve displayed by their striking children. As a direct result of that strike, Prince Edward County was chosen as one of seven defendants in the NAACP’s landmark case seeking school integration, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka.

When the Supreme Court ruled in favor of school integration in 1954, Prince Edward’s supervisors were flabbergasted. It never occurred to them that the court would rule against them. In those days, every important local decision was made not by the supervisors but by a small group of wealthy white men whom sociologist Edward H. Peeples has described as an oligarchy. The group’s spokesman, J. Barrye Wall, then publisher of The Farmville Herald, said it was necessary for the county to close the public schools in response to the high court ruling, to protect the rights of the local government to decide how its own tax dollars would be spent.

At the time, Gordon Moss, a history professor at Longwood University here, was the only white man in town who regularly spoke up for integration of the schools. Wall and Moss had previously been part of a men’s group that met weekly at the Episcopal church.

According to Moss, that is where Wall privately discussed his real feelings about schools and taxes. “[The] primary purpose is to destroy public education for both, yes, the Negro children of the county but also the white children of the county in order that they might maintain an unlimited cheap labor supply for the few, for the industries of the county,” Moss said.

Wall, who died in 1985, never publicly acknowledged that he had spent his life fighting a lost cause. In fact, he declared in a 1979 interview with American Heritage magazine that he expected his point of view would prevail in the long run. “I was and am for separate education for white and black,” he said. “We were defending states’ rights, state sovereignty. The principles for which Lee and the South fought weren’t settled at Appomattox – and still aren’t. The South lost – we lost – but it’s not settled.”

The Prince Edward schools were not forced to deal with desegregation until after the Supreme Court rejected the county’s arguments for a second time in 1958. While other Southern communities briefly toyed with the tactic of closing their schools in response, not one of them did it nearly as long as Prince Edward. When then-Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy came here on May 11, 1964, he irritated the white locals by saying: “The only places on Earth not to provide free public education are Communist China, North Vietnam, Sarawak [a state of Malaysia], Singapore, British Honduras and Prince Edward County, Va.” Even before the public schools were closed, however, the oligarchy established a new private school for white children, knowing that an estimated 1,800 black students would go without education.

The Prince Edward schools were not forced to deal with desegregation until after the Supreme Court rejected the county’s arguments for a second time in 1958. While other Southern communities briefly toyed with the tactic of closing their schools in response, not one of them did it nearly as long as Prince Edward. When then-Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy came here on May 11, 1964, he irritated the white locals by saying: “The only places on Earth not to provide free public education are Communist China, North Vietnam, Sarawak [a state of Malaysia], Singapore, British Honduras and Prince Edward County, Va.” Even before the public schools were closed, however, the oligarchy established a new private school for white children, knowing that an estimated 1,800 black students would go without education.

The long-term effects

The lives of these local black children were forever diminished by the five-year school shutdown. James Lyle, a bright second-grader at the time, said years later that he sometimes still cried as he drove around town in his pickup truck, thinking of the opportunities he had missed. About 70 black children were sent away to attend schools in other parts of the country, but most stayed home.

The Prince Edward Academy – now known as Fuqua School – was established using “tuition grants” given to parents by the state and the county. Classes began in church basements around the county, and a new private school building was in use long before the public schools reopened. After the tuition assistance was ruled unconstitutional, a local bank made loans with easy terms available to those white parents who could not afford the school.

By all accounts, any local person who expressed even the mildest dissent during the shutdown was bullied into keeping quiet. The ringleader for that endeavor was said to have been Charles “Rat” Glenn, a prosperous builder whose company erected the new private school buildings. The late Les Andrews, a former school board member, recalled how he and his children were ostracized because he spoke in favor of reopening the public schools. Andrews said the reaction of the community was particularly unfair, because he had always opposed integration. He only wanted the county to live up to its duty to provide public education.

When the public schools finally reopened in September 1965, only a handful of white children were in attendance. Most of the white parents continued to send their children to Prince Edward Academy. And even though the proportion of white students in public schools has now increased to about one-third, School Board Chairman Russell Dove says they are still somewhat segregated, because whites are routinely placed in the Talented and Gifted program, while blacks usually are assigned to regular or special education classes.

Fuqua might have folded for lack of financial support in the early 1990s, but it was saved when a rich native, J.B. Fuqua, gave more than $10 million to keep it alive. Fuqua President Ruth Murphy, who was hired with the new money, has been able to recruit some African-American students for the private academy in recent years. But Murphy’s efforts to improve the school’s image have never met with the approval of the African-Americans who were denied schooling in the 1950s and 1960s. For them, Fuqua stands as a constant reminder of their own humiliation. Murphy, who often speaks out in favor of racial justice, accidentally made matters worse in the black community recently by telling The Washington Post that when she first saw her newest black student, a football player, she thought he looked like a drug dealer.

In the late 1960s and the 1970s, the public schools recovered from the shutdown better than expected. But the quality of the schools has deteriorated in recent years, and teachers have put most of the blame for that on disruptive black male students. One school administrator said many teachers in the county schools do not believe these boys are capable of learning.

Many children left behind

Many residents were unaware of the growing problems in the schools until 2010, when the high school was designated by the state of Virginia as a low-performer. Until then, the school administrators had been able to paper over many of the problems. So the news came as another surprise, even to those citizens who had been attending school board meetings.

Cambridge Education, a global consulting company, was hired to assist in the turnaround process that is under way in many low-performing schools around the country. Prince Edward County received about $1.5 million over three years from the federal government to implement the turnaround, most of which went to Cambridge. School Superintendent David Smith said the best part of the turnaround was the selection of a new principal and two other top administrators at the high school. Among other things, Cambridge pulled a bunch of students out of the special education program because they were judged as being perfectly capable of earning a regular diploma.

It will be hard for the high school to sustain the results of the turnaround with less money in the budget. Although the county will contribute more than $8 million to the school’s annual budget of $26 million, it refuses to make up for the cut in state spending for schools, which has created a $1.8 million shortfall. The school board has identified numerous teaching positions that are likely to be eliminated because of the shortfall. The school board’s Dove estimated the board would have to cut at least seven or eight teaching positions.

Superintendent Smith said in an interview that while he is disappointed by the funding cuts, Prince Edward Public Schools can still do a good job educating all the children, black and white. “There are many things you can do (for the students) without money,” he said. “The turnaround was one of the best things that could happen to our high school.” The achievement gap that separates black and white students is often misinterpreted by those white residents in Prince Edward County who still believe that African-Americans are not as smart as white people. While that theory has long been discredited, it nevertheless has had an impact on the expectations of teachers and of black students, especially in Prince Edward County.

Robert G. Smith, former superintendent of schools in Arlington, Va., and an expert on the subject of closing the black-white achievement gap, cites study after study proving that the intellectual capabilities of African-American children are undermined in an atmosphere in which they are treated as second-class citizens. It is impossible to imagine any black child could grow up in this county without feeling what former President George W. Bush often called “the soft bigotry of low expectations.”

Narrowing the gap

The Arlington Public Schools and many other successful school districts around the country have succeeded in narrowing the achievement gap by using a race-conscious approach that has never been tried in the Prince Edward schools. Without such training, Smith says, white teachers and even some black teachers do not realize that their expectations for students have been shaped by white middle-class cultural norms that black kids do not always understand. Minority children are often classified as disruptive when they violate these white norms, according to Smith.

In the past, experts believed the best way to make teachers more sensitive to the cultural differences was to teach them more about African-American culture. Smith uses the opposite strategy: He teaches white teachers to recognize how their expectations for student achievement have been shaped by their own lives of white privilege.

Smith’s approach comes from the new field of scholarship known as “whiteness studies,” which began with a 1986 essay by Peggy McIntosh, associate director of the Wellesley College Center for Research on Women, who observed that white people are blind to the existence of white privilege, which they regard as nothing more than the normal way of doing things. Smith acknowledges that discussion of white privilege might be difficult for teachers who have taught for a long time in an environment where racial differences have caused so much pain.

Meanwhile, even though the county supervisors are refusing to raise taxes for public schools, The Farmville Herald has taken a more enlightened view than it did in the 1950s. Herald Editor Ken Woodley has written two editorials recently, calling on the supervisors to listen to the parents and teachers who show up for the annual public hearing on school spending. At the most recent hearing, Woodley said, “Nobody spoke against additional funding (for schools), but somehow Nobody won.”

Sara Fritz, former publisher of Youth Today, is writing a book about the racial history of Prince Edward County.