States should not receive federal funding for foster care if they are not providing high-quality services, caseworkers should not be allowed to hold most visits with youths in front of other adults, and foster children should not be categorized as special education students unless they are going to get the services that classification entitles them to.

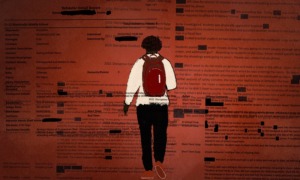

Those proscriptions are among a long list of policy recommendations from 15 former foster children who worked this summer as Capitol Hill interns.

“The Future of Foster Care” was compiled by the Congressional Coalition on Adoption Institute, which oversees the Foster Youth Internship program in Washington. The interns are placed with senators, representatives or with a committee staff.

The first section of the report includes statements from the interns about federal legislative activity that could soon affect child welfare, including reauthorization of the Promoting Safe and Stable Families (PSSF) program and restructuring of federal child welfare financing, most of which is guaranteed to states through the IV-E entitlement administered by the Department of Health and Human Services.

“I feel that when states don’t do a good job we should hold them accountable,” one intern wrote. [The comments are not attributed to specific individuals.] “I think we could create a grant program for states [that] have higher graduation rates for kids in foster care and reward them.”

“States should not be granted federal funds if improvement is not occurring,” another intern said.

In connection with Promoting Safe and Stable Families, several interns suggested that they found little value in their interactions with caseworkers. Many reported having an endless cycle of new caseworkers and described their visits as “mechanical.” The foster children said that visits at which another adult was presented offered little chance for a frank discussion about trouble within their families or in their foster homes.

“I was very involved in school and extracurricular activities and many of my 23 caseworkers did not care if I had a prior meeting or event for school when they asked to see me,” one intern recounted. “The caseworker spent less than 20 minutes asking me questions – the same questions each month – and then would leave.”

Another intern described going once a year to her biological mother’s house “for the 20 minutes that my caseworker would come in the house and inspect.” She pretended to live there so her mom could collect more public benefits, but she really lived with a relative of her previous foster mom.

“I do not remember being asked how I felt and if I was it was very brief and it was in front of my mother so I felt … like I could not say anything,” the intern said.

Each of the interns produced a policy paper focused on one aspect of the foster care system in need of improvement, all of which are included in the second section of their report. For example: 20-year-old Madison Sandoval-Lunn of Las Vegas, who interned for Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nevada) argues that the variation of ways in which states use psychotropic medications with foster children should be of concern.

“Mental health is a medical issue and as such, the needs of children with mental health issues do not vary by state,” said Sandoval-Lunn. “The wide degree of variance suggests that states’ decisions regarding the use of psychotropic drugs are based more on system-level differences than on existing medical best-practice research.”

Other policy papers included in the report discuss accountability in education for foster youth, increasing the role of youths in family court proceedings, and the abuse of children during their time in foster care.

Congressional Coalition on Adoption Institute Executive Director Kathleen Strottman said the piece that most surprised her was by intern Lakeshia Dorsey, 25, a Diamond Bar, Calif. native who interned for the Senate Finance Committee.

Dorsey wrote that foster youth are “both over-represented as well as under-served” in special education services. Foster youth are identified for such services at three times the rate of the general population, Dorsey points out, but often do not have an adult helping them access services to which special education students are entitled.

She suggests that part of the problem may be that “payments are higher for foster youth who are labeled as needing special education.”

The gap between labeling and services “is new to my consciousness,” Strottman said. “I’ve always known that foster kids are getting mislabeled as special education,” but not that they “lack the very services” that special education classifications are supposed to make available.

The Foster Youth Intern program costs about $150,000 per year to operate. Its financial supporters include the Dave Thomas Foundation for Adoption, the Annie E. Casey Foundation and Casey Family Programs, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the American Petroleum Institute.

CCAI also launched its Sara Start Fund for Youth this year, which uses corporate partnerships with D.C.-area businesses to improve the interns’ experiences. The fund helps provide interns with informal career counseling and a stipend they can use for a professional wardrobe.

The fund was established by CCAI advisory board member Lindsay Ellenbogen to honor her grandmother, Sara Rosenberg.

To read the full report “The Future of Foster Care”, click here.