Note: This story was corrected on June 30. The initial story mistakenly reported that Kirk Gunderson had a heroin addiction; he in fact had an addiction to prescription medication connected to multiple injuries he incurred playing high school sports.

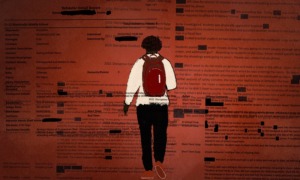

No one is sure why Kirk Gunderson attacked his father and brother on that June day, stabbing them both, causing serious injuries.

His mother Vicky Gunderson believes it was somehow connected with sports – either from the prescription medicine addiction he developed because of repeated sports injuries or possibly brain injuries sustained from the nine documented concussions he had experienced playing hockey, baseball and football at his Wisconsin high school – and as a result of being locked up with longtime criminals.

At 17, Gunderson, a high school junior, was an adult under Wisconsin law. He was placed in the LaCrosse County Jail with other adults, including at one time a sex offender.

“The guy came into the cell and said, ‘I’m gonna have you,’” Kirk told his mother, who relayed the story at a recent meeting on Capitol Hill about juveniles in adult facilities.

In December, six months after he was first ordered to jail, he was placed in a disciplinary area for possessing contraband. Hours later, he was found hanging in his cell.

No data is kept on how often juvenile offenders are victimized in adult facilities. In 39 states, youths under the age of 18 are generally considered juveniles in the eyes of the law, though many have legal exceptions for certain offenses that allow for youths to be transferred into adult court.

Wisconsin is one of just 11 states that set the age threshold for their juvenile court system below 18. It is also the only state that has lowered its age of jurisdiction in decades – pushing the age from 17 to 16 in 1995.

Unlike those transfer exceptions – many of which were passed in the 1980s and 1990s in reaction to an anticipated violent youth crime spree and the killings at Columbine High School – the lower juvenile thresholds in those 11 states came on the books early on in state history.

Last June – five years after Gunderson was sent to jail – the U.S. Justice Department admitted for the first time that the adult system is not an effective deterrent for juveniles, and can lead to higher recidivism rates among them. .

Research over the past decade has shown that young brains don’t reach full maturity until sometime in the person’s twenties – a fact that even the U.S. Supreme Court has taken note of.

There is also mounting evidence that juvenile facilities – by no means an unequivocal success story when it comes to lowering offending – at least keep inmates safe. A federal survey in 2010 found very low levels of nonconsensual sex reported by juveniles in juvenile facilities.

Last year, Connecticut and Illinois became the first two states to raise the age of jurisdiction since 2006. Mississippi joins them this month and there is movement in several other states – North Carolina, New York, North Carolina and Wisconsin – to make similar changes.

What it takes

Putting teenagers back into the juvenile justice system can be a complex undertaking. But in Illinois and Connecticut, other changes that predate the age change have made the shifts easier than expected.

In Connecticut, the change is mostly an unfunded mandate. But because the new law is being phased in – extending just to 16-year-olds first – officials say they have been able to absorb the impact. When 17-year-olds are switched to the juvenile system next year, system leaders say they will have to have more money.

The situation is much the same in Cook County, Ill. – that state’s largest juvenile system – where 17-year-olds charged with misdemeanors were moved into the juvenile system this year, while the budget was being cut. Seventeen-year-olds with felony charges are scheduled to be moved to the juvenile system next year. But now youth advocates are questioning whether the change actually will be better for them (see accompanying story).

If there is a common lesson from the changeovers in Connecticut and Illinois, it is that the states’ earlier reforms to divert younger juveniles into community-based programs have made accommodating a larger number of older teens more feasible economically.

The Connecticut Legislature originally planned to include more 16- and 17-year-olds as juveniles by 2010 when it raised the age of juvenile jurisdiction in July 2007. After local police departments and governments had fiscal concerns about the change, the plan was staggered, moving 16-year-olds into the juvenile system in 2010, with 17-year-olds to join them in 2012.

To oversee the changes, Christine Keller was named chief judge of the state’s juvenile court in May 2007, the second time she had held the position. Keller, a firm believer in raising the age of jurisdiction, was faced essentially with an unfunded mandate – and a law that had technical flaws. For example, 16-year-olds were still legally adults for certain crimes; some of the newly minted juveniles were serving adult probations, and it was unclear who should supervise them.

In the first year with 16-year-olds, Keller said, “we’re seeing about a 25 percent increase overall in the number of cases pending.” The Connecticut Juvenile Justice Alliance estimates that altogether, raising the age of jurisdiction kept 4,000 sixteen-year-olds out of adult court.

The number of juveniles detained before trial rose just 11 percent, while the overall number of cases rose by 25 percent. But detention quickly involved an older population; Keller said 16-year-olds now make up about 40 percent of detained youth.

The court didn’t track the age of youths in detention until recently, said Connecticut Judicial Branch spokeswoman Rhonda Hebert, “but it was a very small number” of 16-year-olds in detention before the age change.

The only money that was added to the juvenile budget was to be used to hire three new probation officers. That office turned out to need help the least. Julia O’Leary, deputy director of the Court Support Services Division, said the probation numbers actually went down, even as 16-year-olds were added to the system.

However, other areas of the juvenile justice system felt the pinch. With no new placement slots and no additional public defenders or prosecutors, Keller said, the court staff has been overworked as more offenders must be accommodated in the same number of spaces.

The capacity problems are predicted to get worse next year with, an influx of 17-year-olds. The lack of options for juveniles deemed to need residential treatment or incarceration means longer waits for placement, which, in turn, increases the number of juveniles in detention.

“I’m getting worried about the placement issues,” Keller said. “We need more substance abuse treatment than we ever needed before, and we’re trying to do some vocational-type probation programs. We have the training school, but it only takes boys.”

What came before

The placement shortage could have been a crisis in Connecticut, if it weren’t for state juvenile policy changes that preceded raising the age. The state eliminated the valid court order exception, a loophole in the federal rules prohibiting detention of status offenders that allows judges to detain juveniles for violating court orders related to status offenses.

The practice was eliminated in 2007; the year before, 498 status offenders were detained using the valid court order exception. Abby Anderson, executive director of the Connecticut Juvenile Justice Alliance (CJJA), estimated it saved the state about $2 million a year leading up to the age change.

O’Leary said the probation department also developed a pre-trial case-review process well before the age change, which she said significantly lowered the number of offenders headed for placement.

The reviews focus on determining which youths could be served in the community, an option that has become more viable since 2007, when Connecticut established family support centers around the state to provide such services.

The review process has driven a decline in the number of placements from about 700 juveniles per year to 200, O’Leary said.

“If we had the detention centers full, the way they had been,” O’Leary said, the age change could have been a catastrophe.

“There was a lot of concern that this would overwhelm the system,” said Anderson. “About the same number of 16 year-olds we anticipated did come in. But we didn’t realize just how much different programs and services around diversion and early intervention had worked.”

The addition of 17-year-olds to the juvenile justice system is scheduled for July 2012. There is $7 million in the first year of the state’s biennial budget for the judicial branch to accommodate that change. About $2 million will pay for new staff, including 37 new detention workers and nine more probation officers, as well as seven mental health staff members.

Much of the remainder pays for non-incarceration placements, including home-based services, job training, substance abuse, family support centers, mentoring and a male youth leadership institute. A total of $4.8 million is in the budget for 2013.

The budget that includes these funds has been signed by Gov. Dannel Malloy (D), but it assumes billions of dollars in concessions from state unions that have not been secured.

Cook County, Ill.

Unlike Connecticut, which may follow a small bump in resources with a significant increase next year, the pool of potential juveniles in Cook County – Chicago is the county seat – swelled in 2010, as the budget for services declined.

A 2009 state law sent 17-year-olds charged with misdemeanors to juvenile court, effective in January 2010. At the same time, appropriations for the Cook County Juvenile Probation and Court Services Department, which had been consistently $38 million a year, dipped to $34 million for fiscal 2011.

In the first year under the new rules, police in Cook County referred 3,494 seventeen-year-olds on misdemeanor charges. In almost 70 percent of those cases, the Office of the State’s Attorney did not file charges.

Five hundred forty-five other cases were diverted from the formal juvenile court process and sent to Juvenile Probation and Court Services (JPCS) for informal supervision.

The remaining 554 cases were filed in court, but probation officials said that did not add much to the caseload.

“A lot of the kids that we got had been sent to us already,” as opposed to 17 year-olds who had no previous run-ins with the juvenile probation department, said John Bentley, a project administrator with Cook County JPCS. “That doesn’t add much additional burden.”

So far this year, Cook County is on pace for a lower number of referrals, filed charges and diversions. However, the percentage of cases in which charges are filed is rising slightly.

Years before the age change, Cook County had embraced the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative, which assists jurisdictions and states in developing a risk measurement instrument to help determine detention admissions.

While its Juvenile Temporary Detention Center – designed to hold 500 – once held 600 or more, by the middle of 2010, the facility’s population had dropped below 200 for the first time in 20 years, said center administrator Earl Dunlap. Right now it’s at about 265, which, he said, is not attributable to an influx of 17-year-old juveniles with misdemeanor offenses.

“The impact has been negligible” on the detention center, said Dunlap.

He credited the county juvenile probation office for “how much of the minor stuff is shifted out.” He said that when he took charge of the detention center in 2007, about half of the population probably didn’t need to be detained. Now, he believes, the percentage is down to about 25 percent.

The state juvenile justice commission is studying the impact and cost of moving 17-year-old felons into the juvenile justice system, and will produce a final report by December.