|

|

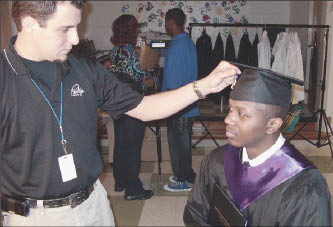

Capping it off: A photographer adjusts the tassel on the graduation cap of Jonathan Wade, 19, on senior picture day at Fuller Performance Learning Center. |

Fayetteville, N.C.—The thick scrapbooks that counselor Dawn Holt keeps in her office make it clear that young lives are being changed here at the Fuller Performance Learning Center, an alternative high school for youths who once had no hope of graduating on time.

There’s the typewritten speech given by Taylor Shackleford, the 2008 salutatorian, who just a year or so before had been locked away in a juvenile detention center in Georgia.

“I look forward to what my future holds,” wrote Shackleford, who now studies at a community college in Wilmington, N.C.

There’s a letter congratulating 2008 valedictorian Dinesha Neal, a foster care alumna, on being chosen to receive a $1,300 college scholarship. Neal, 19, is secretary of the Student Government Association at Fayetteville Technical Community College.

Developed by the nonprofit Communities In Schools, Fuller Performance Learning Center is one of 36 such schools, also known as PLCs, nationwide. The schools – which feature small class sizes, self-paced online learning and college prep and college credit courses – are being hailed as a model for dropouts and other students who have fallen so far behind that high school graduation would otherwise be out of the question.

Statistics show that PLCs are getting dropouts and far-behind students to graduate from high school and go to college. Of the 3,227 students who have graduated from PLCs since the first one opened its doors in Atlanta, Georgia in 2003, 58 percent continued with some form of post-secondary education, 12 percent joined the workforce, and 6 percent joined the military, according to Communities In Schools.

Here in this military city, Fuller PLC is also showing some early success: Last year, all 28 seniors graduated. The school reports that 20 are enrolled in community colleges, six are in jobs and two are in the military.

“We took kids who were totally disengaged from education and now have been continuing” to higher education, said Cindy Kowal, executive director of Communities In Schools of Cumberland County, N.C.

Communities In Schools is expanding PLCs in Georgia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Virginia and Washington with a $9.9 million grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation – part of the foundation’s efforts to increase the number of youth who graduate from high school and go on to earn a post-secondary degree.

Results

Fuller PLC got started with a $100,000 grant for technology and a $10,000 grant for furniture, both from the Gates Foundation through Communities In Schools. The one-story, seven-room school is funded through Cumberland County’s regular public school system. Students must apply to the school and interview with administrators.

The National Dropout Prevention Center at Clemson University in Clemson, S.C., recently rated the PLCs in Georgia as having “strong evidence of effectiveness.” (The Georgia sites, which are the oldest, are the only ones to be so evaluated.)

“Their design is excellent,” the center’s director, Jay Smink, said of the PLCs.

ICF International, a Fairfax, Va.-based global consulting and technology firm, evaluated PLCs in Georgia for Communities In Schools there and concluded that PLCs are an effective model. An evaluation (www.cisga.org/plc/plc_results.php) released by ICF last month said graduation rates in school districts with PLCs were 6 percentage points higher after two years than in districts without PLCs.

Some data, however, are underwhelming. For instance, under the North Carolina School Report Cards online school data system, Fuller’s test scores are much lower than the average for the Cumberland County School District. Also, Fuller has been cited for failing to make “Adequate Yearly Progress” under the federal No Child Left Behind law.

Fuller counselor Holt said that designation has more to do with testing mandates of students who were underperforming before they got to Fuller than what takes place within the school. Smink said it will take a few more years to better assess the effectiveness of PLCs compared with regular schools.

In contrast to traditional schools, students at Fuller PLC get a large portion of their lessons through an online system called NovaNet; early on, some youths received all of their lessons that way.

Principal Terry McAllister said the students did well on the computers but had shortcomings, such as trouble applying the theories behind the concepts they were learning. Fuller supplemented NovaNet with more instruction from teachers and McAllister said the students showed improvement as a result.

McAllister is confident that the students who graduate from PLCs are ready for college. By the time they graduate, he said, the students have had opportunities for job shadowing, apprenticeships, internships and service-learning.

Personal Touch is Key

Beyond test scores and ratings, there are elements of PLCs that are hard to quantify but that Smink and others say are crucial to students’ success. Chief among those is the quality of relationships that the small-school design enables PLC staffers to build with students, whose lives have often been so besieged by problems – such as fighting in school, family breakups and poverty – that focusing on school became increasingly difficult. The staff of 15 includes eight teachers, a counselor and a social worker.

Talk to the students here, and it’s clear that many believe that they now have teachers who care.

“It’s more of a family instead of a school,” said Francisco Moran, an 18-year-old junior from Camden, N.J., where, he reports, he used to “hustle in the streets” and went to school to sleep.

Moran dropped out of high school and cooked at Burger King, until he decided there was no future in earning $7 an hour and hanging out with other dropouts. An aunt invited him to move in with her in North Carolina. At Fuller, he said, teachers encouraged him to believe in himself.

“They always have your back,” Moran said. “They understand. They care, like parents or close friends.”

McAllister, whom students affectionately call “Mr. Mack,” counts strong relationships as a key element of Fuller’s success in re-engaging students who have become disengaged from formal education.

“Once we’ve established a relationship and students know it’s genuine and sincere, they’re going to meet expectations that are set for them, in terms of student achievement, academic performance, test scores getting better, because they’ve found someone that is there for them,” the principal said.

“If you have a student who has a child and they don’t have bare essentials, school is not important,” McAllister said. “We do our best to find resources,” such as financial aid for child care.

That approach impressed Amber Laroche, a 17-year-old junior who recently enrolled at Fuller. Laroche worried about how she would be viewed when she told “Mr. Mack” that she was a mother.

“He said, ‘Don’t worry about it. You’ll graduate,’ ” Laroche recalled, as tears welled in her eyes. “I cried. I never had a principal be so relaxed and not just look at you like you’re going to mess up.”

She said McAllister involved her child’s father in the discussion and got her connected with child care. She leaves school early on some days for her job as a cook at Little Caesar’s, but the school’s self-paced design enables her to keep up with her coursework.

Laroche is on track to graduate next year.

Contact: Fuller PLC (910) 488-6262, http://www.fplchs.ccs.k12.nc.us; Communities In Schools (703) 519-8999, http://www.cisnet.org.