|

|

Children with developmental and learning disabilities often report social rejection by their peers. Research suggests that, for some of these children, the problem rests with their inability to accurately process nonverbal social cues. The failure to distinguish subtle facial expressions, for example, sets these children up for increased social isolation. The Social Competence Intervention Program (SCIP) offers a hands-on, drama-based approach to social skills training.

Target Population

Designed to help children improve social competence skills, SCIP targets children diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome, High Functioning Autism, and Nonverbal Learning Disabilities. It’s suitable for children between 8 and 14; the developers recommend grouping children into narrower age ranges to accommodate maturity levels and self-esteem issues.

Although designed for youth who are designated with these disabilities, this curriculum can be used to help many youths who might be described as socially awkward, or who for a variety of reasons have trouble making and maintaining friendships.

Goal of Program

SCIP facilitates understanding of nonverbal components of communication. Youth are taught explicit skills for observing nonverbal social cues, and they then use a creative drama process to practice social problem-solving.

Length of Program

Run as a 16-session program, individual SCIP workshops last approximately 1½ hours. The curriculum recommends holding two sessions a week. Compacting the schedule helps with retention of what is learned and gives participants more opportunities to successfully build their budding social skills.

Resources and Materials

SCIP relies mainly on handouts and pencils for many activities. However, users should assemble a box of standard craft supplies for occasional projects. Space considerations need to be balanced by the number of children in the program. Some of the activities require ample space for children to move about energetically, so floors should be free of furniture.

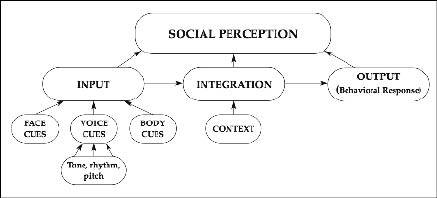

A diagram from the curriculum explains key concepts. |

Process drama activities require an assortment of props and costumes that take some time to gather. The authors point out that a costume can be as simple as a garbage bag and a belt. A video camera and television for on-demand playback adds a critical element to the feedback process.

Training

A one-day training session is necessary for staffers without special education backgrounds. In addition to background information on the target population, the curriculum guide provides behavior management information. By examining the issues that drive misbehaviors characteristic to this group, the materials offer effective group management techniques to aid successful implementation of the program. Staff training helps to keep everyone on the same page with behavioral expectations.

Prep Time

Most workshop sessions require minimal preparation time. Group leaders should schedule at least one hour to prepare for the process drama workshops. Due to the unpredictable nature of process drama, leaders should take time to discuss possible outcomes.

Program Highlights

SCIP divides sessions into three essential concepts. “Input” focuses on the perception of social cues. “Integration” concentrates on piecing cues together within their social context. “Output” devotes time to practicing skills within the group.

Each workshop includes a warm-up activity, numerous interpersonal activities and a large group discussion. Most activities within a session are short and varied enough to hold youths’ interest.

Communication with parents is essential in order to reinforce the learned skills. A weekly Home Challenge activity gives participants an opportunity to practice skills with family and friends. Students are asked to write a journal at home about the experience. Follow-up discussions offer children an opportunity to share successes with their peers and accept group feedback. The Home Challenge reviews and general discussions emphasize a meta-cognitive approach to social skills learning. SCIP takes the “how” of social skills and extends it to include “why” certain skills work better than others. This added dimension offers an important empowerment tool for the children. Instead of automatically reacting in a programmed way, children begin to develop the wherewithal to make more meaningful social decisions.

The authors stress that the creative drama activities are about process, not dramatic product.

Leaders modeling flexibility with the social outcome of a particular workshop is as important to the program’s goals as sticking to the script.

Watch out for …

The authors note activities that may present certain programming challenges. For example, children who resist being touched may be reluctant to participate in Sculptors and Clay. This activity requires one child to nonverbally guide another child’s body into a particular model, such as a hungry dinosaur. Alternative directions are suggested to keep kids engaged and still meet learning objectives.

During its development, the program met with unexpected obstacles to some of the drama activities. The issues appeared to be more a factor of poor social skills rather than deficits with the program. Nonetheless, building this experience into the curriculum, the authors present alternative scenarios for handling “plot twists.”

Empirical Support

SCIP is the product of the principal author’s dissertation, completed at the University of Texas, in Austin. The program was developed to help children who experience social difficulties as a result of misperceptions of social interactions, rather than because of issues with aggression and anger or self-regulation.

Laura Guli conducted a series of clinical program trials in 2002, comparing the effects of SCIP to a control group. Clinical trials maintained a workshop leader-to-child ratio of at least 1-to-2. While none of the quantitative or qualitative measures produced significant results, appreciable improvements were noted in the SCIP students. Youths reported an increase in confidence with their social interactions outside of the group. Parents reported an increase in the appropriate use of such social skills as apologizing.

Overall, initial results for SCIP appear to be promising. As the authors continually point out, flexibility with implementing the program is a key to success. Group leaders are encouraged to model how to adapt to the unexpected. Doing so can lend a dynamic element to the group discussions that make up every session. Such observational learning on the student’s part may not necessarily be evident eight weeks later on a paper-pencil behavioral measure.

Interestingly enough, the original trials presented the program in fewer sessions. The curriculum manual, however, offers enough original material for the program to run longer than the proposed 16 sessions. Given the benefits of additional practice in a controlled setting, program leaders can easily extend their program with little effort.

Alessandra Giampaolo is a curriculum developer in Reisterstown, Md. Contact: agkeener – at – aol.com