The Bernalillo County Juvenile Detention Center in New Mexico is but a speck on the map of the nation’s juvenile justice system. It handles a few hundred of the 26,000 youth held in detention on any given day. As in every other detention center, many of the youths suffer from mental health problems.

|

|

The mental health clinic is not much to look at, but its funding strategy has experts talking. Photo: Nicol Moreland |

Nevertheless, national associations and major foundations are talking about what this center has accomplished.

Bernalillo has built a better mousetrap – in this case, one that enables it to tackle one of the most vexing struggles in juvenile justice: how to pay for and provide mental health services. At a time when most juvenile detention centers struggle to pay for basic mental health services, Bernalillo even built an community mental health clinic on its site.

What’s more, the whole operation is supported by something that every detention center might be able to get: Medicaid funds.

Tapping the Medicaid pipeline is about as easy (or difficult) as getting a state official to write a letter that says the payments are allowed under federal rules.

But there are roadblocks, none more daunting than this: Youth Today research suggests that the vast majority of the relevant state officials don’t even know that Medicaid funds can be used this way. Another issue is political support for the idea at the state level.

That helps explain why the success of the Medicaid-infused clinic puts Bernalillo County in a class with … nobody, according to juvenile justice reform expert Bart Lubow, who leads the Annie E. Casey Foundation Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI), for which the county is a model site.

“There aren’t any” detention centers providing the kind of comprehensive mental health services found at the Bernalillo center, Lubow says.

Finding a Way

Back in the 1990s, detention center Director Tom Swisstack saw that he had a mental health problem on his hands. The center holds up to 78 males and females awaiting adjudication or placement elsewhere, and at any given time half of them were identified with mental health problems. After release, that group had an 88 percent recidivism rate.

As with many detention centers, a mental health system was in place for the youths – technically. Youths were referred to local residential treatment centers (RTC), but with stays at the center averaging 52 days, many of the youths were released before getting into an RTC. Those who got in actually fared worse: They were more likely to re-offend than youth released to outpatient care, according to the center’s data.

Swisstack had an idea about how to better address the needs of his youths with mental health problems: Bring mental health services into the detention center complex.

So in 2001, two portable buildings appeared next to the center – one provided by the county and one donated by Kirtland Air Force Base. The buildings reside on the same grounds as the detention center – a large campus with no fencing or barbed wire. The only secured building is the detention lock-up itself; the youths are walked from there to the clinic.

Getting those buildings to operate as a clinic required money and staff. Swisstack pursued several strategies:

• He persuaded the county not to cut back on the detention center’s funding, even though the center’s population had been dropping, thanks to an approach under Casey’s JDAI that used new measures to determine whether an arrested youth should be detained.

• He spent some of that extra money on contract workers for the mental health clinic, including three behavioral health therapists. Swisstack reassigned some front-line workers to clinic positions. One was trained to be the receptionist, and two were sent to school with county funding to become trained case managers, according to Nicol Moreland, who conducts research and statistical analysis for the center.

• The detention center entered a partnership with each of the state’s three major providers of Medicaid: Presbyterian Health Care, Lovelace and Cigna. Tracey Feild, who studied the project four years ago for a report for the Annie E. Casey Foundation titled “Meeting the Mental Health Needs of Youth in Juvenile Detention,” recalls that Swisstack told the providers, “We can reduce the reliance on residential treatment if you give us some money to start up in-home services programs” – meaning outpatient services organized by the clinic.

“They got the money,” Feild says, “and residential care costs went way down.”

But what really enabled the clinic to make a big difference for detained youth was Medicaid money.

A Costly Assumption

To understand why using Medicaid for this purpose is novel, you have to know why government officials think they can’t do it.

Many juvenile justice administrators assume that Medicaid funds are not available for services in their facilities. That belief stems from one Medicaid rule, which says federal matching funds are not available for “expenditures for services provided to individuals who are inmates of public institutions.”

So the idea that detained youth could even be considered Medicaid eligible is news to officials in most states, according to research by Youth Today. (See list, page 15.) In 34 states, officials in charge of juvenile justice or Medicaid administration said they consider every youth in detention centers to be ineligible for Medicaid.

That points to the standard lack of communication and partnership between juvenile justice systems and Medicaid.

“There’s no consistency, even within states,” on Medicaid’s role in juvenile justice, says Shelly Gehshan, a senior program director with the National Academy for State Health Policy. Among state juvenile justice agencies, she says, “Medicaid is considered byzantine.”

As for Medicaid officials, it’s not as if they’re cutting off juveniles to save money. Very few state Medicaid offices report doing anything to find out who’s in detention so that the state can discontinue their coverage.

“It’s not that we look the other way,” says Claude Gravois, a Medicaid program specialist for the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. “We just don’t look.”

In Louisiana, Gravois says one detention center director allows youths who were receiving Medicaid benefits when they entered the facility to continue refilling prescriptions through Medicaid.

It was this dilemma – youth receiving no mental health services or waiting a long time for residential treatment that was often ineffective – that motivated Swisstack to make a change.

Aggressive About Medicaid

In 1999, before he even had his clinic, Swisstack had made the case to the state Medicaid office that the federal definition of inmates excludes anyone “in a public institution for a temporary period pending other arrangements appropriate to his needs.”

The Medical Assistance Division of the state’s Human Services Department agreed to let Swisstack keep youths eligible for Medicaid for 60 days.

After the clinic opened, Swisstack and State Rep. Rick Miera (D), who worked part-time as a therapist for the clinic, got the office to put that in writing. “An individual who is placed in a detention center is considered temporarily placed until adjudication or up to 60 days, whichever comes first,” wrote the state’s Medical Assistance Division director, Carolyn Ingram, in 2005.

From the time it got the verbal OK for Medicaid billing, the detention center was aggressive about winning Medicaid eligibility determination for its youth. That’s why the center’s nurse became the second stop for incoming youth, after booking. What the center does at this point might be unique among juvenile detention centers: It signs up youth who are found to be eligible for Medicaid on the front end of its entry process. The center is authorized to enroll them with pre-qualification status, so Medicaid availability kicks in right away.

That opens the tap for Medicaid to pay for the overwhelming majority of youth who come through the center’s doors. Last year, the clinic billed New Mexico Medicaid $329,000, accounting for 75 percent of the clinic’s revenue. The clinic has also been able to bill Medicaid for medical care at the center, Moreland says.

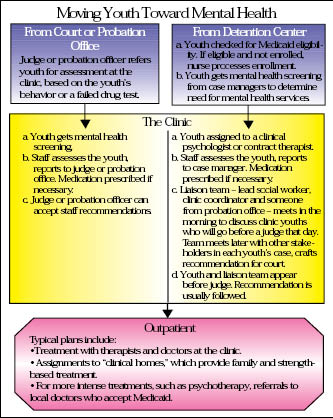

Besides coming from the detention center, youths also come to the clinic on the basis of referrals by probation officers and judges. Many youths’ treatment plans include continued visits with clinic staff on an outpatient basis, even though they’ve been released from the center or were never detained there. (For a description of how youth flow through the clinic system, see chart.)

The average length of clinic outpatient treatment is 70 days, Moreland says. Most youth who need longer, more intense treatment are referred to outside professionals who accept Medicaid.

Results

In fiscal 2007, 159 juveniles were referred to the clinic, then discharged from the detention center. Fifty-six percent had been convicted of serious charges involving crimes against a person, theft and possession or use of a weapon; 18 percent had been convicted only on drug or alcohol charges; and 26 percent were brought in on “petty misdemeanor offenses.”

Within six months of their release, 53 of those youths had returned to the detention center with new charges, for a recidivism rate of 33 percent. Before the clinic opened, the recidivism rate among youths identified with mental health problems was 88 percent.

Among the 53 who returned, 1 percent of the charges filed against them were for person, property or weapons crimes.

In addition, the average length of stay for youths at the center dropped significantly: from 33 days in 2000 to 10 in 2007. Observers say the mental health care is a major reason.

“It’s just been remarkably successful,” says Feild, now director of consulting engagements for the Casey Foundation.

As word has gotten out about the success of the Bernalillo model, why haven’t more detention centers followed it?

Hard Act To Follow

The clinic has hit snags along the way. At first, it was open to the public as well as to the detention center, to assuage concerns that youth who broke the law would have access to better mental health care than the general population.

That arrangement didn’t work, however, because juveniles ended up waiting to be seen, just as they had waited to get into RTCs.

Another problem persists: Most juveniles at the clinic are referred by probation officers or judges. Moreland says this is “somewhat problematic, because it’s untrained people referring kids for mental health,” which means the clinic staff screens a fair number of youth who, it turns out, don’t need its services.

There is also a legitimate question about the notion of mental health services conducted in the detention setting, a debate the Bush administration is trying to settle by curbing use of Medicaid money in the juvenile justice system. (See Youth Today, April 2008, page 14.)

But with social program dollars dwindling nationwide, advocates are taking note of this Medicaid/juvenile justice nexus. The National Association of Counties has taken several delegations on visits to the facility. The National Academy for State Health Policy has received a $475,000 grant from the MacArthur Foundation to help improve coordination and collaboration between the Medicaid and juvenile justice systems in the four states participating in MacArthur’s Models for Change juvenile justice reform initiative.

Meanwhile, although officials in 34 states told Youth Today that detained youth are ineligible for Medicaid, officials in 10 states said they think all of their pre-adjudicated youth are eligible. A few of those 10 are starting to forge connections between the juvenile justice and Medicaid systems, while others might just need a push. Colorado would allow its juvenile detention centers to bill Medicaid, according to Joanne Lindsay, public information officer for the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing.

|

But nobody has tried yet, she says.

And no one knows what would happen if, nationwide, detention centers started billing their states for hundreds of thousands of dollars in new Medicaid reimbursements. (Swisstack says New Mexico has had no problem collecting federal matching funds for the work done by the clinic.)

“This is labor intensive at the beginning,” Swisstack says. Even with the state’s permission, the process would never work without strong relationships with Medicaid, and a staff that is fluent in Medicaid billing and paperwork.

“You really have to build bridges and discuss things based on data and dollars,” he says.

Contact: Juvenile Detention Center (505) 761-6600, http://www.bernco.gov/live/departments.asp?dept=2337.