Program evaluations that use randomly assigned control groups are touted as the gold standard, but a major drawback is that those in the control group are left out of the program. That’s why such an evaluation of a 42-year-old program for poor kids has ignited a heated debate over ethics and funding that has reached an unusual level: Congress versus the Bush administration.

Congress banned the U.S. Department of Education (ED) from funding the control group evaluation for Upward Bound, but the department continued the evaluation anyway.

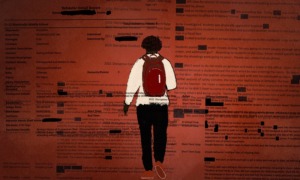

At issue is which is the lesser of two ethical evils: Recruiting at-risk youth for a “life-changing” program, then banning some of them from participation so they can serve as the control group, or touting a program as “life-changing” in the absence of scientific evidence that it produces positive outcomes for most participants?

Those questions could eventually confront other youth programs, as federal and foundation funding is increasingly tied to scientific evaluations of their impact.

Evaluation Required

Upward Bound began in 1965 as a pre-college support program for low-income youth. It’s the oldest of the three initial federal TRIO programs, which are aimed at helping disadvantaged students get to college.

The approximately 800 Upward Bound programs, most based at colleges and universities, serve 60,000 students in grades 9 to 12 at an annual cost of about $5,000 per youth. The program offers academic instruction, cultural enrichment, counseling, mentoring and other services to help youth graduate from high school and enroll in college. For the past three fiscal years, it has been funded at about $278 million annually.

A five-year evaluation of Upward Bound completed in 2000 by the research firm Mathematica found very limited effects for the program overall, but said it made a substantial difference for the most academically at-risk students.

For that reason, the ED enacted regulations in September 2006 requiring that 30 percent of all students admitted to Upward Bound be ninth-graders “at high academic risk for failure” – a requirement known as “Absolute Priority.”

The rule mandated an evaluation of Upward Bound by the Urban Institute, Abt Associates and Berkeley Policy Associates, and required programs funded in fiscal 2007 to follow the “Absolute Priority” for 2007-08.

The evaluation design said about 3,600 youths would be randomly assigned to either Upward Bound or to a control group that would not receive Upward Bound services. Programs were required to recruit double the number of students for which they had open slots, so as not to reduce the number of students they could serve.

The trouble began soon after the 101 participating Upward Bound programs began recruiting youths for the evaluation.

Too Painful?

Some programs had trouble recruiting twice as many students as usual, according to the Council for Opportunities in Education (COE), a membership association of colleges, universities and agencies that host TRIO programs. That left some serving fewer youths than they were funded for, said COE spokeswoman Susan Trebach. For example, a program with 50 slots that recruited only 70 students could serve only 35 of them.

More troubling, Trebach said, was that the application process is involved and lengthy for the families, and that “the applicants and their parents are generally persuaded [by recruiters] that this will be a life-changing experience. So the recruiting is not done casually.”

Trebach said Upward Bound staff members reported that youths assigned to the control group were “devastated,” particularly after they were told they were ineligible to reapply for any Upward Bound services.

“So it’s a double whammy really, because some kids are just outright disappointed, and other kids don’t even have the opportunity to compete, even if they’re not part of this evaluation,” Trebach said. “So we felt very strongly, and we heard from our community very strongly, that this particular model was very abusive to students. And you didn’t get the money unless you agreed upfront to do it their way.”

Program evaluators deny that the evaluation is abusive. “Every piece of research that’s done that involves data collection goes through our institutional review board in order to protect the rights of individuals,” said Jane Hannaway, director of the Educational Policy Center at the Urban Institute.

Hannaway said the random assignment design was appropriate and necessary.

Killing it Loudly

|

|

Werner: “We’re really sort of in a gray period right now.” |

In August 2007, the Chronicle of Higher Education ran a story about Upward Bound in which COE president Arnold L. Mitchem compared the evaluation to the Tuskegee experiments, in which government researchers secretly withheld treatment from a group of 400 black men with syphilis in order to test treatments. The evaluators wrote a letter to the editor calling Mitchem’s comments “unfair” and “unhelpful,” and insisted that Upward Bound recruits and their parents were informed about the possibility of being assigned to a control group.

COE’s government relations division lobbied sympathetic congressmen to intervene. Last fall, with the backing of Sen. Barack Obama (D-Ill.) and Sen. John Kerry (D-Mass.), Sen. Sherrod Brown, (D-Ohio) introduced an amendment to the Senate’s 2008 proposed spending bill for Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education to eliminate funding for the evaluation.

The amendment became law when President Bush signed the appropriations bill in December, which seemed to kill the evaluation.

Stayin’ Alive

But according to Alan Werner, a principal associate at Abt and the project director for the Upward Bound evaluation, Secretary of Education Margaret Spellings determined that the money supporting the evaluation was not fiscal 2008 funding, because the programs were initially funded earlier.

“If a site happens to contact us, we have been instructed to tell them … that the evaluation is ongoing, and that if you want to bring kids in now, you have to do it through this lottery. You can’t enroll them directly,” Werner said. “We’re really sort of in a gray period right now.”

ED officials declined to comment on the issue.

COE is lobbying Congress to reauthorize a version of the Higher Education Act that would eliminate funding for the evaluation and would also eliminate the use of “Absolute Priority.” The most recent extension for the reauthorization expires on April 30.

Some evaluation experts say the ED went about this all wrong: that the choice of such a rigorous design was too threatening for Upward Bound’s advocates, coming on the heels of attempts to eliminate TRIO funding in 2006 and 2007.

“For the two previous budget cycles, they’ve tried to kill it,” COE’s Trebach said. “So excuse us if we’re less than entirely confident that this was all about wanting to improve Upward Bound.”

She said other evaluation designs could be used measure the program’s effectiveness.

Jon Baron, executive director of the Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy at the nonpartisan Council for Excellence in Government, said one alternative to large-scale evaluations of federal programs would be to evaluate the effectiveness of particular strategies or site models, with an eye toward replicating best practices.

“That kind of approach is often not threatening … because it’s trying to build knowledge about which approaches within the program work,” Baron said.

Other experts said the evaluation would have been less controversial if programs could have volunteered for the study, instead of having participation tied to funding.