Let’s say your program jumps on the evidence-based bandwagon and spends lots of time and money to develop a high-tech performance measurement system to help you track and evaluate your outcomes.

It’s complex, so you spend even more time and money on training and technical assistance. After a few costly years of getting the system up and running, and using it to make financial, policy and programming decisions, an outside evaluator looks at your program’s performance.

The verdict: “Adequate.”

Whether you manage a community-based agency or administer a large federal one, the question at that point is the same: Is this thing working?

That’s the question for the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) after the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) conducted a Program Assessment Rating Tool review of its formula and competitive grant programs.

After investing millions of dollars over several years in the development of its online Data Collection and Technical Assistance Tool, its Model Programs Guide and Database, and a host of technical assistance and training tools for grantees, OJJDP just got back its rating: “Adequate.”

The program “needs to set more ambitious goals, achieve better results, improve accountability or strengthen its management practices,” OMB said.

Results

The OMB reviews, known as PART, were instituted by the Bush administration and have been a source of fear and debate among federal officials. They are designed to identify the strengths and weaknesses of programs, in order to inform funding and management decisions and to improve the programs.

Aside from “adequate,” programs can be designated as “effective,” “moderately effective,” “ineffective” or “results not demonstrated.”

|

Since 2002, ninety-six percent of federal programs (977 of them) have been assessed. Of those, 17 percent were rated “effective,” 30 percent were rated “moderately effective,” 28 percent were rated “adequate,” 3 percent were rated “ineffective,” and 22 percent were found to have undemonstrated results.

Evidence that those ratings affect funding decisions remains, well, undemonstrated. A 2003 “results not demonstrated” rating for the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign was followed by a funding increase, from $99 million in fiscal 2006 to $130 million in fiscal 2008. On the other hand, a 2006 “effective” rating for the Runaway and Homeless Youth program in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has yet to pay off: Its funding remained at $103 million over the same period.

For the review of its Juvenile Justice Program grants, conducted in 2006 and released in February, OJJDP responded in detail to 25 questions, based on years of performance measurement data, which had been provided by state grantees and sub-grantees.

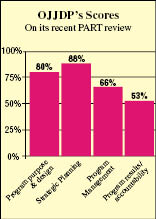

The results (listed in the box on this page) ranged from a high of 88 percent for strategic planning to a low of 53 percent for program results and accountability.

OMB noted that OJJDP had “developed a number of resources … for states and localities to promote the implementation of effective practices and program models” and that “the programs still compare favorably with other programs focusing on juveniles, delinquency and crime.”

The review found significant weaknesses, including a funding distribution system that does not effectively provide resources to states and localities based on need or merit. In fiscal 2006, for example, only 14 percent of Juvenile Justice Program grants were awarded on a competitive basis, according to OJJDP.

(Much of the blame for that problem can be laid on Congress, which has jammed OJJDP’s budget with earmarks.)

The program also got low scores because its budget requests to both OMB and Congress, as well as its own internal requests to the Department of Justice, are tied weakly or not at all to the achievement of performance targets, and because its grantee performance data are not made available to the public in a transparent and meaningful way.

The greatest weaknesses were in program accountability. OJJDP reported mixed performances by programs in achieving long-term and annual performance goals for both 2005 and 2006.

For example, the grant programs as a whole met their 2005 goal of having 37 percent of youth exhibit a desired positive change in a targeted behavior; however, OJJDP estimated that by the end of 2006, only 26 percent of its grantees had implemented evidence-based programs – a long way from the 2006 goal of 46 percent.

In its response, OJJDP noted that while it has not undertaken a scientific evaluation of its major programs, it has funded several evaluations, including those of the Safe Schools/Healthy Students Initiative, the Truancy Reduction Demonstration Program, and the Gang Free Schools and Communities Program. It has also contracted with researchers to assess how well the programs that get funds through congressional earmarks can be evaluated, and it has sponsored efforts by Blueprints for Violence Prevention to rate its programs for how well they can be replicated.

The Right Focus?

This is not the first time OJJDP has gotten a less than effective rating by PART. In fact, it’s not even the agency’s worst grade.

A 2002 PART review of OJJDP’s Juvenile Accountability Block Grants program rated it “ineffective.” The review concluded that overly broad funding criteria and minimal reporting requirements made it difficult for the Department of Justice to target spending or determine how grantees should use program funds.

Since then, OJJDP seems to have embraced the concept of process improvement. It has required all of its grantees to collect and report data that measure the results of funded activities.

But reporting at that level requires quite a bit of training and technical assistance. According to a 2004 audit by the Justice Department’s inspector general, the department’s Office of Justice Programs awarded $312.5 million in technical assistance and training grants to 158 contractors from fiscal 1995 to fiscal 2002. They help grantees and sub-grantees report annually to either their states or to OJJDP’s online data collection tool.

That process is tedious at best. It involves training grantees to select from a pre-approved list of measures, models and evidence-based practices, and to report standardized outcomes into a rigid system that’s ultimately used to measure their funder’s performance against OMB’s entirely different set of standardized criteria.

“If this [reporting] is being done as a way of refining and improving the way the federal government serves in a support role to state and local communities … then I’m all for that,” said former OJJDP Administrator Shay Bilchik, director of the new Center for Juvenile Justice Reform and Systems Integration at Georgetown University. “But if they’re using it to become accountability czars … then they’re really not serving youth.”

Bilchik said that despite the criticism of the block grants in the 2002 PART review as “overly broad,” the program at that time was purposely designed to give states flexibility.

“It’s ironic to me that the system that’s been developed in the last six or seven years is one that is finding that approach to be unsatisfactory,” he said.

OMB’s Juvenile Justice Programs Assessment is available at www.expectmore.gov. Type “Juvenile Justice Programs” into the name/keyword field.