First lady Eleanor Roosevelt and her friend were afraid, and they didn’t mind letting the three dozen people gathered with them in the East Room of the White House know it.

“I must confess to all of you that I am thoroughly frightened,” declared Aubrey Williams, executive director of the National Youth Administration (NYA). “I think we are fighting with our backs against the wall all over this country.”

It was Oct. 27, 1941. In the six years since its creation, the NYA had grown into the closest thing the country had ever had to a comprehensive national youth development program, providing millions of young people with jobs and job training, community service work, recreation, remedial education and real-life lessons in the blessings of democracy at a time when democracy was fighting for its life.

But the agency had made powerful enemies – most dangerously, Washington’s education establishment. Months after the NYA’s advisory committee heard Williams’ warning at the White House, Congress cut the agency’s budget and debated killing it altogether. Within two years, the NYA was history.

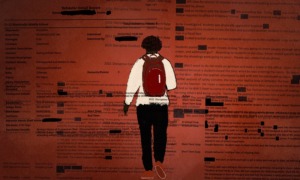

Like much of the youth field’s history, however, this story is fading from memory. It is difficult to find any youth worker or administrator who’s even heard of the NYA.

President Lyndon Johnson, who had directed the NYA in Texas, called it an ancestor of Great Society programs such as Job Corps and Upward Bound. Robert Taggert, former director of youth programs at the U.S. Department of Labor, says that when he researched Great Society programs in the 1960s, he first studied New Deal programs like the NYA and realized, “We’re doing the exact same thing.”

The NYA tried to be far more than an employment training program, reaching out to dropouts, partnering with schools and providing civic engagement and life skills training.

But its ambition contributed to its death. Six decades later, its rise and fall offer insight into the often uneasy dance of education and youth-serving agencies today as they try to cooperate while competing for federal dollars and program control.

The story is told through decades-old records at the National Archives outside Washington and the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park, N.Y., and the work of several historians.

Youth in the Depression

Every year, youth advocates publish reports about “The State of America’s Children” (Children’s Defense Fund) and “Profiles of Child Well-Being” (the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s “Kids Count Data Book”). If these reports had been around during the Great Depression, they would have said this:

In 1935, an estimated 2.9 million youth lived in families that were receiving government relief.

Hundreds of thousands of them had stopped going to school, primarily because their families didn’t have money for supplies or decent clothes, or because they had to find whatever work they could. The same reasons compelled more and more young people to drop out of college as well.

They found jobs to be scarce. The nation’s unemployment rate hit 29 percent in 1933. In 1935, slightly more than 5 million youth were out of school and unemployed – about the same number as today, according to Northeastern University’s Center for Labor Market Studies, although the population of 15- to 24-year-olds was about 56 percent of today’s 39 million.

Idle youth were a common sight, making adults uneasy about the kids and the country’s future.

U.S. Education Commissioner John Studebaker warned that a “youth left idle becomes open to the impulses that lead into crime and dishonest rackets.” Two NYA observers wrote that “the plight of youth had been dramatized by the thousands of boys and girls who had taken to ‘bumming’ their way around the country.”

The undereducated and unskilled youngsters could hardly be counted on to pull the nation’s economy in the years ahead. And government leaders feared that idle youth were vulnerable to political inculcation by communists and socialists. How much value could these youngsters place in democracy and capitalism if those systems had left them impoverished, uneducated and jobless?

“Young people were now questioning the very fundamentals of the American economy,” one historian notes. One poll of college students found that four out of five said they wouldn’t fight for their country if it went to war abroad, and 16 percent said they’d sit by even if the country was invaded.

President Roosevelt’s advisers looked at youth across the Atlantic and shuddered. Italy had its Youth Fascist organization. The Soviet Union had its Communist Union of Youth. And Germany had the Hitler Youth, with enrollment reaching 5.4 million in 1936. Members of Roosevelt’s brain trust, such as American Molasses Co. President Charles Taussig, noted that “tyrants abroad … were turning European youth against democracy, exploiting the idealism native to all youth and demonstrating how easily America’s youth might suffer a similar experience.” Taussig was among those urging Roosevelt to create a national youth program to instill the values of democracy.

These advisers also saw in such a program an opportunity to fix something they despised: the American educational system.

The School Problem

To many in the administration, the plight of American youth was largely the result of an educational system that ignored the needs of the poor – providing them with the worst teachers and supplies and providing little vocational-related education to help them get jobs. Administration leaders shared the observation expressed decades later by Richard Reiman, a historian of the NYA, who notes that “leading educators, obsessed by a crisis that existed largely in their own imaginations – the myth of an imminent radical takeover of their profession – were largely ignoring the real crisis of angry but reluctant dropouts.”

Education leaders did talk about how to “bridge the gap between school and employment.” But schools could hardly afford innovation. The Depression put “a tremendous strain upon our educational system,” noted a 1940 report from the Federal Security Agency. “Local and state revenues fell. … Teachers’ salaries were cut or remained unpaid for months at a time. … School terms were shortened from nine to six or seven months.”

Combating these problems with a federally controlled youth program was fraught with political peril. Public and congressional fears about indoctrination of youth would bring any federal effort under attack as a Nazi-like regimentation scheme. And the education establishment, particularly the National Education Association (NEA), treated anything that looked like federal control of education as an invader to be quashed.

Shock Therapy

Roosevelt had partially addressed the problem by creating the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in 1933. While popular, the CCC was limited: It accepted males only; it required youth essentially to go away to live in the woods while working on conservation projects; and it was primarily a manual labor relief program that was not set up to provide education or much job training.

The Roosevelt administration wanted something more ambitious and inclusive – something that would provide money to help students stay in school, training to help out-of-school youth get jobs, and services to mold young people into involved and productive citizens.

Would it be primarily an education program or a relief program? That question set off a power struggle between the Office of Education and the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which laid the foundation for the NYA’s future troubles.

The two agencies spent months drafting competing proposals. Studebaker, the education commissioner, “vigorously opposed the creation of any new federal agencies to work with youth.” He went public with a proposal for a national Community Youth Program that would steer students in educational matters, job training and employment – even for dropouts. “It is … faulty to assume that education’s responsibilities are confined to the classroom,” he said in one radio address. His plan would use “the existing machinery of the public school system, adding to that system and joining other groups with it as may be necessary.”

Ironically, the protectionism of education leaders may have turned their paranoia into self-fulfilling prophecy. Studebaker’s objections to involvement by the WPA reinforced the perception among that agency’s leaders of “school officials as people possessed of an almost medieval hostility to reform, conservatives anxious to protect, guild-like, their prerogatives as deliverers of American education.”

Many in the Roosevelt administration didn’t believe those leaders would devote more resources to poor youth and to job training unless they were forced to. Presidential advisers “wanted to shock an American educational establishment … into accepting a halfway revolution of the nation’s educational curriculum,” Reiman writes.

The WPA proposal developed under the guidance of Administrator Harry Hopkins and his deputy, Aubrey Williams, initially included the education office as a limited partner, but even that was ditched in response to Studebaker’s campaign for his education-only plan. The WPA plan was more ambitious in its aim to fully develop young people, not just give them jobs. And it won the support of Taussig of the American Molasses Co. and the first lady.

In June 1935, the president issued an executive order creating the NYA. It encompassed aspects of several plans, but was to operate under the WPA and be administered by Williams.

Williams was, in the words of one chronicler, “a passionate, liberal Alabamian.” He had a degree in social service from the University of Cincinnati and had worked overseas with the YMCA.

The president gave the education office a seat on the agency’s executive committee – a move designed to placate educators, because power at the NYA actually rested with the National Advisory Committee. The advisory committee was chaired by Taussig and composed of representatives from fields such as labor, agriculture, religion and education – the latter coming from colleges and the American Federation of Teachers, not from the federal education office or the NEA.

Many teachers and school administrators supported the NYA because it provided money for kids to stay in class and because the NYA kids’ work included upgrading schools. But George Strayer of Columbia University’s Teacher’s College spoke for many higher-ups in the education bureaucracy when he told the New York Times: “The president has not only deliberately ignored the office of education,” but he “has denied the competence of the school people with their years of experience and has set up a dual administration dealing with youth guidance.”

Innovations

Anyone who feared the NYA probably found comfort in its first annual appropriation: $50 million in emergency relief funds from the WPA, with renewal to be considered annually. The sum and the uncertainty of future funding left NYA leaders bemoaning the fact that they could do little more than rush to provide a few hours of community service work to a fraction of the youth who needed it, let alone offer any real youth development programming, such as citizenship activities.

At the first conference of state directors, in August 1935, one disappointed director stressed that rather than just provide work, it was essential “to create first in the youth a feeling of a personal – now I underscore personal – interest in them.” This sense of personal attention to youth permeated throughout the NYA’s internal discussions.

The agency ran two major programs: part-time employment for youth in school, including college students (ages 16 to 24), and an out-of-school work program for unemployed youth (mostly 18 to 24).

The in-school program primarily involved public works projects that otherwise might not have been done, such as renovating schools. The idea was not only to provide money for youth but to keep them out of the overcrowded job market – important for fending off objections from organized labor.

The youth were chosen according to need: Being from a family on relief was the primary indicator. The median annual income of the NYA students’ families in 1939-40 was estimated at $645 – about $8,584 in today’s dollars.

For those in school, earnings were limited to $6 a month for primary and high school students, and $20 a month for undergraduate college students. For out-of-school youth, the average monthly earnings ranged, for example, from $15.27 in 1936 to $18.37 in 1939.

Two aspects of the NYA stood out. One was its residential camps. While most NYA youth lived at home, thousands of mostly rural youth lived at the camps, which provided lessons in employment, independent living and leadership. Youths paid for their food and clothing, ran the households and elected local leadership councils.

The other was its outreach to blacks. To Reiman, the NYA created “the first federal affirmative action program in history” – reflecting the view of Williams and his fellow administrators of their agency as an engine for social change. In 1936, for instance, the NYA held a conference on “Government Policy and the Problem and Future of the Negro and Negro Youth.” The agency’s “negro division” was headed by educator Mary McLeod Bethune, and many of its local programs were either all-black or integrated.

The youth worked at a countless array of jobs, many of which were at their own schools: painting, repairing or even building schools, building student desks, constructing running tracks and tennis courts, and refurbishing books.

NYA youth also built piers for a recreational lake in Redfield, S.D.; renovated a boys’ club in Pawtucket, R.I.; constructed tuberculosis isolation huts in Arizona; developed a cross-pollination orchard in Ontario, Calif.; and visited the homes of poor kids in Waco, Texas, to see why they were missing so much school.

No one spread the word of this work more than Mrs. Roosevelt, who encouraged her husband to create the agency and became, as one biographer wrote, its “chief adviser, chief publicist, chief investigator.” She conferred daily with Williams, invited him to dinner with the president and visited NYA sites.

No detail was too small for her involvement. Witness her letter to Williams in 1941 about a controversy that had arisen within the agency over a man being considered for a supervisory position in Patterson, N.J: “If this man is really good I do not think he should be turned down because he is a republican.”

She knew the NYA needed all the political support it could get, for it was constantly being tugged in different directions. Notes Reiman, “The NYA was continuously recast to meet the needs of a society lurching from depression to war.” This evolution would be the key to its growth, and to its trouble.

Bitter Enemy

NYA leaders knew their agency was built on politically vulnerable ground, being one of the New Deal’s alphabet-soup concoctions. Right from the start, Williams’ office kept a newspaper clipping file in which articles were coded according to the papers’ political leanings, and compiled weekly summaries of media coverage. Most of the early press was favorable. Criticisms were labeled as coming from one of three categories: educational, political (Republicans) and youth groups, primarily far-left organizations, such as the American Youth Congress, which found the agency doing too little for too few.

The NEA was officially supportive. In June 1939, NEA Executive Secretary Willard E. Givens wrote to local educators in support of the NYA’s budget request, saying that if they were “interested in increased appropriations for needy youth, now is the time to let your representatives in Washington know.” NYA funds, he noted, “have helped many thousands of worthy girls and boys to continue their work in secondary schools and colleges.”

Yet the NEA eyed Williams’ agency with all the comfort of the family dog watching a new puppy sniff at its dish. Consider the bureaucratic tiff between Williams and Education Commissioner Studebaker in 1936.

An NYA board member had suggested that the agency conduct a national survey “of the youth problem to secure as much data as possible on the needs of deprived young people and their difficulties in securing employment.” Roosevelt agreed, but Studebaker “saw the dread hand of a relief agency involving itself in something that was properly the concern of his office.” He protested to the president, who agreed to let the education office administer the survey, with the NYA cooperating.

Victory for Studebaker – until Williams told Roosevelt the whole thing was a waste of money. The president pulled the plug, infuriating Studebaker.

The conflict took on significance well beyond the issue at hand, for it stirred the animosity between the two agency leaders. Williams, according to his biographer, considered Studebaker “perhaps the most bitter enemy he ever made during his years in Washington.”

Space Invader

The problem was that for certain people in Washington whose jobs were to guard their constituents’ turf, Williams was constantly sneaking into their territory.

When his agency established guidance and placement bureaus in 1936 to help young job seekers, and when it began training youth for war production as World War II loomed, some labor leaders charged that the youth would replace older, veteran workers at cheaper wages.

When rural youth moved away to NYA residential programs near centers of employment, farmers charged that the agency was luring young laborers away from agricultural work.

Educators, however, had more reason to worry than anyone.

The NYA’s leaders felt that much of the youths’ early work, such as building parks, was nice community service but failed to tap the agency’s potential to help young people in the long term. They believed “the direction should be away from relief and toward the setting up of a new type of training agency, a second-chance education scheme that would provide permanent skills for deprived youth, which would enable them to fit into the mainstream of their economic and social communities.”

In a 1936 press release about upcoming NYA programs, Williams stressed that “the emphasis on the work projects would henceforth be to give training. The labor-intensive projects, such as park maintenance or recreation work, were to be scaled down and replaced with more solid skilled activities.”

The NYA was stepping into vocational education – which schools saw as their bailiwick, even though many educators admitted that they did it infrequently and poorly. Williams knew this was dangerous ground; he instituted the changes slowly while reassuring educators that his agency was no threat to them. The agency stressed that its local projects were conducted in cooperation with state and local education officials. For the in-school programs, the schools typically chose the youth involved, approved the work projects and disbursed the money.

But the tense peace was shattered in 1939, when Roosevelt shored up the NYA by moving it from its status as an emergency program under the WPA to be an established office within the Federal Security Agency – signaling that the NYA, rather than being a temporary relief experiment, was a permanent government function. The president’s statement to Congress amounted to a virtual red flag in the faces of some education leaders: It said the NYA’s “major purpose is to extend the educational opportunities of the youth of the country, and to bring them through the process of training into the possession of skills which enable them to find employment.”

Seeing the NYA declared an “educational” agency involved in “training” confirmed for the NEA that the federal government was slowly moving to centralize the nation’s educational system.

What’s worse, the NYA paid the youths for the training as part of their work, which the schools could not do, making the NYA work more attractive. And the NYA often got new equipment to carry out the task, while the schools struggled to maintain their own shopworn equipment.

In a letter to Williams years later, the NEA’s Givens said he initially supported the NYA, “but when the NYA began to move into the field of education, as it did as early as the summer of 1938, and became a federal agency of vocational training and general education, I considered it to be my duty as executive secretary of the nation’s education association to oppose all such moves.”

That opposition was aided by the threat of war.

War Footing

With Adolf Hitler rolling through Europe and America debating if and when to join the war against him, virtually every agency in Washington was thinking about how a war would change its work.

Williams didn’t wait for war; he saw defense-related work as a matter of survival.

As early as 1938, he began shifting the work done by youths at the residential centers toward tasks that would be useful for defense contractors, such as making machine parts and building engines. As the situation in Europe worsened, Williams accelerated the shift throughout the NYA. By 1940, the agency noted in one of its annual reports, “the NYA began to function primarily as a defense training agency, with its facilities concentrated upon the task of equipping youth with the specific abilities required by those industries engaged in the mass production of defense materials.”

The NYA’s defense work is one reason its expenditures rose from $39 million in 1936 to $155 million in 1941.

While many agencies were shifting toward defense preparation out of fear for the nation’s well-being, some agency leaders had other motivations. As the nation drew closer to war, the hunt was on in Washington to eliminate any government function that was not absolutely necessary.

Politics played a role as well – especially among conservative Republicans, who had gained congressional seats in 1938 and set out to roll back many of Roosevelt’s New Deal creations.

The NYA was in the cross hairs. After all, its raison d’être was disappearing. The economy was picking up steam, thanks to defense production, creating thousands of jobs for young people. And with radios, newspapers and dinner table conversations increasingly filled with talk about the threat to democracy from overseas, Reiman notes, the need for the NYA “as a schoolhouse for citizenship responsibility was no longer so apparent as before.”

That year Williams tried to neutralize his biggest foe, signing an agreement with Studebaker that gave education officials responsibility for off-the-job training of NYA enrollees. “In the short term,” writes Williams’ biographer, “the agreement mollified Studebaker … without greatly restricting the NYA’s education activities,” which were largely on-the-job training.

Then the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.

Hitler and Deer Hunters

Even before Dec. 7, 1941, the NYA was staggering – witness the October meeting at the White House where Williams said he was “thoroughly frightened.” While the complaints against the NYA had circulated primarily among federal agencies and the education establishment during the 1930s, the critics got more publicly aggressive with their charges shortly before the attack on Pearl Harbor and revved up their assaults after.

The strategy was reflected in newspaper coverage. Two weeks before the White House gathering, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette wrote of the NYA: “Its present effort to conduct a national system of vocational training points to a dangerous course of centralized control of education which, carried to its extreme, results in such propaganda systems as those of Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini.”

At about the same time, the Scotland Neck Commonwealth in North Carolina wrote, “The educators are foaming at the mouth because someone else is doing what they should have done long ago. … We are glad someone had the courage to urge fuller education to make a living for those who never finish high school.”

The following two years brought a series of reports from various agencies, along with congressional hearings into cutting nonessential government expenditures, that accused the NYA of everything from stealing government money and undercutting farmers to hunting for deer and fostering interracial sex:

• A U.S. General Accounting Office investigation raised numerous charges against the NYA, including claims that it lured youth from school with promises of jobs, used agency resources for personal business (such as excessive calls from office phones) and abused travel expenses. The last charge centered on an NYA official’s trip to Montana, where someone reported he had gone deer hunting. This prompted an affidavit to Congress from a Montana administrator, who swore that “never at any time did a member of the NYA national or regional staff accompany me or any other member of my staff on a deer-hunting trip, and further that I never took such a trip with one exception during my tenure in office … and not during office hours.”

• A scathing 79-page report from the NEA and the American Association of School Administrators charged that the NYA had sneakily crept from being a temporary relief program to being a permanent education agency controlled by Washington – setting up the frightening prospect of centralized control of the nation’s educational system. It recommended transferring much of the NYA’s funding to the Office of Education and gradually eliminating the agency.

• A report by the American Association of School Administrators and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Committee on Education said, “The National Youth Administration should be discontinued. The use of its equipment should be transferred to local and state authorities, and operated under U.S. Office of Education direction.”

• Another U.S. Chamber of Commerce report (this one from its agriculture committee) charged that the NYA “has recruited

substantial numbers of its ‘unemployed’ youth from farms and rural communities,” thus “placing a further strain on the nation’s already inadequate farm labor supply.”

• Charges from a congressman that an NYA center in Auburn, N.Y., was essentially a social club for whites and blacks prompted telegrams to Congress from NYA supporters, such as this one from a minister who regularly visited the center: “I wish to deny that Negro boys are encouraged to court white girls or that the center is a negro white socializing institution. … All relationships are carefully supervised.”

• Givens of the NEA rallied state education associations to lobby their congressional representatives to kill the NYA, writing in a May 1943 letter: “Unless the NYA is eliminated now, we have a competing federal agency in the vocational field, duplicating the work being done better by the public schools at a cost that is unreasonable. … Whatever you do must be done at once.”

Survival Mode

Williams fired back with language that reflects the more angry sentiments of some youth agency leaders today.

“This attack is an effort on the part of a small group of educators here in Washington to kill off every effort that serves young people, except that which they control,” he wrote to Sen. Burnet Maybank (D-S.C.) in the wake of Givens’ letter. “They assume that no one but the self-appointed spokesmen of organized education has the right to carry on any effort for the purpose of extending opportunities to young people.”

The NYA’s survival strategy was to drum home two points to Congress and the public: that it was cooperating with local school officials, many of whom supported it, and that its youth training was necessary for the national defense.

Thus, while the NYA’s early promotional videos showed smiling NYA youth cultivating crops and painting buildings, it now produced videos with titles such as “Youth, Jobs and Defense,” showing youths working on planes and submarines.

With proposals floated in Congress to eliminate the NYA in 1941, 1942 and 1943, Williams routinely testified on Capitol Hill and sent letters and reports to congressmen. Typical was a 1941 report that stressed the NYA’s “close working relationship with the local public schools.” NYA youth had built or renovated more than 13,000 education buildings, said the report, which noted that local school officials “plan the student work projects, select and assign students and supervise student NYA workers.”

Congressmen also got letters from businesses throughout the country testifying to the important contributions of NYA youth to the production of materials and equipment related to the war. These were offset by letters from education officials accusing the NYA of hoarding materials and underutilizing equipment because its centers couldn’t recruit enough youths.

The agency’s fate came down to the complicated maneuvering that comes with the annual federal budget approval in Congress. With a proposal from Sen. Harry Truman (D-Mo.) to fund the NYA at $48 million, the Senate voted in the summer of 1943 to include the agency in the 1944 budget. The House did not include the agency in its budget. When the two sides hammered out a compromise spending plan, it did not include the NYA.

The war and economic recovery may have killed the NYA even without the push from the education industry. What will never be known is if the education industry would have won without the war.

Legacy?

The impact of any program can be measured in part by numbers. From 1935 to 1943, the NYA provided work to more than 2.1 million students and to nearly 2.7 million young people who were out of school. The agency spent a total of $467,586,000 – less than $100 per youth.

While President Johnson spoke of the NYA as a predecessor to Great Society programs, Reiman writes that among federal policy-makers, “the NYA was discussed rather condescendingly as a well-meaning exercise in organized compassion, but lacking the expert understanding of the sociological and psychological roots of poverty.”

Even those in the youth field who are familiar with the NYA struggle to find its long-term influence. Taggart, the former Labor Department administrator, says this reflects the field’s tendency to reinvent concepts of how to serve youth every decade or two, while ignoring history and labeling those ideas as new.

Reiman notes that the agency ushered in a new way to deal with youth in their transition to adulthood, going beyond the outdoorsy physical regimen typified by many programs in the early 20th century (such as the Boy Scouts) to focus more on practical independent living and job skills.

What’s particularly striking is how the agency stressed youth assets half a century before the concept would be widely prompted as a guiding principle for youth work. When examining the NYA in 1938, the U.S. Advisory Committee on Education noted that the agency “has uncovered a reservoir of competent youth desirous of continued education, for whom almost no provision has been made in the past. …

“By providing youth with an articulate agency for the expression of their needs and a focal point of direct action in meeting them, the National Youth Administration has helped to restore their morale.”

Patrick Boyle can be reached at pboyle@youthtoday.org.

A sampling of nondefense work performed by NYA youth.

Arizona: Built portable tuberculosis isolation huts for the state board of health – 7- by 9-foot cottages with screened openings.

Arkansas: Repaired government automobiles in Solgohachia.

California: Developed experimental cross-pollination fruit orchard in Ontario.

Florida: Built school for black youth in Campbellton.

Idaho: Did library and clerical work in Coeur d’Alene.

Kansas: Made mattresses for state welfare department in Topeka.

Kentucky: Cared for sick students in dorms at the Lincoln Institute in Lincoln Ridge, a school for black youth. Repaired and painted more than 1,500 rural schools.

Mississippi: Canned, sewed and cooked in Piney Woods.

New York: Helped develop New York City’s public parks – spread topsoil, laid drainage and water lines, built retaining walls.

Ohio: Studied stream flow, to aid conservation and flood control, through Ohio State University.

Oklahoma: Built eight-room community center in Paul’s Valley for use by Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, 4-H.

Rhode Island: Renovated Pawtucket boys’ club.

South Dakota: Landscaped artificial lake in Redfield. Built 200-foot boardwalk, a pier, two diving towers.

Texas: Visited homes of underprivileged children in Waco who had been absent from school, to determine the reason for their absence.

Utah: Constructed 6-inch reflecting telescope at a high school in Payson.

Wisconsin: Constructed school furniture in Chippewa Falls.

Sources: A New Deal for Youth, Final Report of the National Youth Administration.

Resources

Books

A New Deal for Youth: The Story of the National Youth Administration, by Betty and Ernest K. Lindley, Viking Press, 1938.

A Southern Rebel: The Life and Times of Aubrey Willis Williams, by John A. Salmond, University of North Carolina Press, 1983.

Eleanor Roosevelt, 1933-1938, Vol. 2, Blanche Wiesen Cook, Viking Penguin, 1999.

Planning the National Youth Administration: Citizenship and Community in New Deal Thought, dissertation by Richard A. Reiman, University of Cincinnati, 1984.

The New Deal and American Youth: Ideas and Ideals in a Depression Decade, by Richard A. Reiman, University of Georgia Press, 1992.

Reports

NYA Diversion of Manpower, Chamber of Commerce of the United States, March 1943.

“Eleanor Roosevelt and the National Youth Administration,” Presidential Studies Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 4, 1984.

Final Report of the National Youth Administration, U.S. Federal Security Agency, 1944.

The Civilian Conservation Corps, The National Youth Administration and the Public Schools, National Education Association and American Association of School Administrators, undated.

Reduction of Nonessential Federal Expenditures, National Youth Administration, Joint Committee on Reduction of Nonessential Federal Expenditures, 78th Congress, 1st Session, Document 54, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1943.

Wartime Vocational Training, American Association of School Administrators and Chamber of Commerce of the United States, undated.

Sources

The documents cited below are from the National Archives and Record Administration in College Park, Md., and the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park, N.Y. For full information about book and report titles listed below, see Resources.

“I must confess …” Minutes of NYA National Advisory Committee Conference, Oct. 27, 1941.

“2.9 million youths …” President Roosevelt remarks at meeting of NYA state directors, Aug. 20, 1935.

“Most of the youth on relief …” FDR remarks at meeting of NYA state directors, Aug. 20, 1935.

“… more than five million youth were out of school …” Remarks Prepared for Father Moore for Use in Preparation of National Advisory Committee Report to the President, Jan. 23, 1942, p. 6.

“By 1937 …” Final Report of the National Youth Administration, pgs. 12-13.

“Education Commissioner John Studebaker warned …” Radio address by J.W. Studebaker, “The Dilemma of Youth,” April 30, 1935.

“…the plight of youth had been dramatized … ” Lindley, Betty and Ernest K., A New Deal for Youth, p. 11.

“Young people were now questioning …” Reiman, Richard A., The New Deal and American Youth, p. 43.

“One poll of college students …” Salmond, John A., A Southern Rebel, p. 141.

“Germany had the Hitler Youth …” Reiman, p. 34.

“ … tyrants abroad …” Ibid, p. 32.

The School Problem

“leading educators, obsessed by a crisis …” Ibid, p. 32-3.

“… bridge the gap …” Ibid, p. 89.

“ … a tremendous strain upon our educational system …” NYA Student Work Program, report by the Federal Security Agency, June 1940.

Shock Therapy

“Education Commissioner Studebaker ‘vigorously opposed …’ ” Salmond, p. 182.

“It is … faulty to assume … ” Radio address by J.W. Studebaker, “The Government’s Interest in Youth,” Feb. 20, 1935.

“…the existing machinery of the public school system … ” Radio address by J.W. Studebaker, “The Dilemma of Youth,” April 30, 1935.

“…school officials as people possessed …” Reiman, p. 4.

“…wanted to shock an American educational establishment …” Ibid.

“… a passionate, liberal Alabamian …” Beasley, Maurine, The Eleanor Roosevelt Encyclopedia, p. 367.

“He had a degree …” Reiman, p. 47.

“The president has not only … ” Ibid, p. 218.

Innovations

“At the first conference of state directors …” National Youth Administration, Conference of State Youth Directors, Aug. 20, 1935.

“The median annual income …” Activities of National Youth Administration, 1935-40, U.S. Department of Labor, May 1941.

“For out-of-school youth, the average monthly earnings …” Final Report of the National Youth Administration, p. 117.

“… the first federal affirmative action program …” Reiman, p. 2.

“In 1936, for instance, the NYA held a conference …” Cook, Blanche Wiesen, Eleanor Roosevelt, Vol. 2, 1933-38, p. 412.

“… chief adviser, chief publicist, chief investigator.” Ibid, p. 270.

“If this man is really good …” Letter from Eleanor Roosevelt to Williams, July 2, 1941.

“The NYA was continuously recast …” Reiman, p. 188.

Bitter Enemy

“…NEA Executive Secretary Willard E. Givens wrote to local educators …” Givens letter, June 7, 1939.

“An NYA board member had suggested …” Salmond, p. 128.

“… the most bitter enemy …” Ibid.

Space Invader

“…the direction should be away from relief …” Salmond, p. 131.

“…the emphasis on the work projects …” Ibid.

“… the NYA’s ‘major purpose is to extend …’ ” Final Report of the National Youth Administration, p. 27.

“…but when the NYA began to move …” Givens letter to Williams, June 22, 1943.

War Footing

“… the NYA began to function primarily …” National Youth Administration Annual Report, 1942, p. 3.

“… expenditures rose from $39 million in 1936 …” Final Report of the National Youth Administration, p. 240.

“.. as a school house for citizenship responsibility …” Reiman, p. 7.

“In the short term …” Salmond, p. 145.

Hitler and Deer Hunters

“Its present effort …” Weekly Summary of Editorial Comment on the National Youth Administration, Oct. 18, 1941.

“The educators are foaming …” Weekly Summary of Editorial Comment on the National Youth Administration, Nov. 1, 1941.

“…never at any time did a member of the NYA …” Affidavit of James. B. Love, Oct. 13, 1941.

“the NYA ‘has moved into the field of education …’ ” The Civilian Conservation Corps, The National Youth Administration and The Public Schools, pg. 77.

“The National Youth Administration should be discontinued …” Wartime Vocational Training, p. 2.

“… the NYA ‘has recruited substantial numbers …’ ” NYA Diversion of Manpower, March 1943, p. 2.

“I wish to deny that Negro boys …” Western Union telegram, Rev. Joseph McNamara, June 16, 1943.

“Unless the NYA is eliminated now …” Givens letter to “state education associations,” May 27, 1943.

Survival Mode

“This attack is an effort…” Williams letter to Maybank, June 16, 1943.

“…close working relationship with the local public schools …” Remarks Prepared for Father Moore for Use in Preparation of National Advisory Committee Report to the President, Jan. 23, 1942, pgs. 32-34.

Legacy

“From 1935 to 1943, the NYA provided work … ” Final Report of the National Youth Administration, pgs. 54, 109.

“… the NYA was discussed rather condescendingly …” Reiman, p. 195.

“… the NYA “has uncovered a reservoir …” Johnson, Palmer O., and Oswald L. Harvey, The National Youth Administration, U.S. Advisory Committee on Education, 1938.